Parasites are never fun, and certainly less so when they affect your own cat or kitten. Parasites can rob your cat of good health, making her more susceptible to infections and diseases. In addition, many parasites are zoonotic, meaning they can cause problems in people as well. A diagnosis and recommendations for treatment from your veterinarian are the best way to manage parasites once they have taken hold, but it can also be wise to treat your cat with prophylactic medications to prevent parasitic infections.

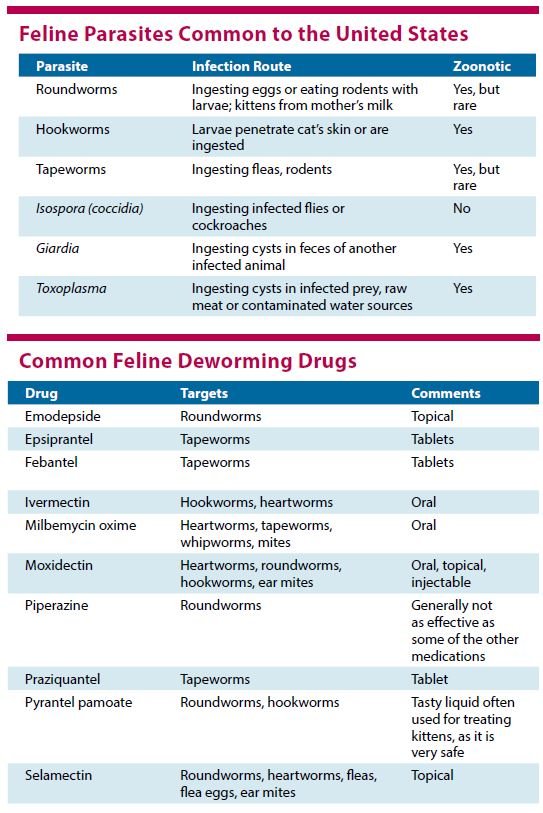

This article focuses on the most common feline parasites. See the chart below for other possible parasitic infections in cats.

Common Roundworms

Toxocara cati is the most common feline roundworm, or ascarid, found in cats, affecting more than 25 percent of all cats. Kittens can become infected by nursing from queens that are infected. More commonly, cats and kittens become infected by ingesting infective eggs from a contaminated environment or eating other vertebrate hosts that have larvae in their tissues.

This means that a cat who walks through an infected area and then licks her feet or a cat who catches and eats a mouse or bird could be infected with ascarids. For this reason, cats who go outdoors have a higher risk of infection and reinfection than indoor-only cats.

Once eaten, larvae migrate through the tissues of a cat’s body, especially the liver and lungs. They develop to adulthood in the small intestines of an infected cat. While in the small intestines, the adults produce large numbers of eggs, which are passed with the feces and contaminate the areas they end up in—from litter boxes to your yard. Ascarid eggs are quite hardy and can survive in the environment for years.

Kittens with an ascarid infection often appear “potbellied,” in spite of the fact that they can lose lean muscle mass. The parasites drain nutrients that the kittens need to grow and develop normally, so affected kittens may fail to thrive and grow normally. Some cats will show respiratory signs, such as coughing, if large numbers of larvae migrate through the lungs, while others may experience vomiting and diarrhea when the worms reach the stomach and intestines.

Diagnosing an ascarid infection usually requires finding parasite eggs in the feces of an infected cat. Occasionally, a cat with a heavy infection will vomit up an adult worm, in which case it should be saved in a sealable plastic bag and taken to your veterinarian for identification. Parasite eggs in the stool can’t be seen with the naked eye, so microscopic evaluation of the feces is required.

Typical drugs used to treat roundworm infections in cats include both topical and oral preparations. Your veterinarian may choose pyrantel pamoate for kittens, as it’s a tasty liquid and very safe. (See drugs chart on page 4.)

Many veterinarians recommend that cattery owners, rescue groups, and shelters start by deworming kittens every two weeks from two weeks of age on up until eight weeks of age. After that, kittens can go on monthly treatments.

Adult cats should be treated as needed, based on fecal evaluations. A single dose of deworming medication is usually not adequate to eliminate roundworms because most dewormers act on the adult worms in the intestines and do not catch the migrating larvae. This is why multiple doses over time are required to eliminate these larvae as they reach the stomach and intestines.

A concern with any infection—bacterial or parasitic—is the development of resistance by the infectious agent to the drugs used to treat the problem. Fortunately, drug resistance is not a major concern for cats with roundworms at this time.

“There are currently no consistent reports of treatment failures for common roundworms in cats and dogs that cannot be accounted for by the biology of the worms or by re-infection. Therefore, if resistant isolates exist—and there is literature to support that this can happen—they are not widespread. Any cat shedding roundworm eggs in their feces should be dewormed and broad-spectrum parasite control should be instituted,” explains Dr. Araceli Lucio-Forster, from the department of Microbiology and Immunology at the Cornell University School of Veterinary Medicine.

A big concern with ascarid infections in pet cats is that people are also susceptible to these parasites. Infective eggs are commonly found during screenings of outdoor areas, including playgrounds and public parks. Ascarid eggs can survive for years in the environment and serve to infect both animals and people. Children are especially susceptible, as they are often play on the ground or dig in sand pits. Accidental ingestion of dirt contaminated with larvated Toxocara eggs can lead to human infection. Feral cats and wildlife are generally considered to be the source, but pet dogs and cats can contribute, too.

Syndromes in people infected by Toxocara include visceral larva migrans (caused by larvae migrating through the abdomen and possibly causing signs of liver disease), neural larva migrans (caused by larval migration through the nervous system), and ocular larva migrans caused by larvae migrating through the eye and possibly resulting in loss of vision).

Dr. Lucio-Forster stresses that parasite control is important both for your cat and your family. “At Cornell, we recommended that all animals be on year-round broad-spectrum parasite control, such as monthly heartworm disease preventives with label coverage of roundworms. Any animal shedding roundworm eggs in their feces should be dewormed, and broad-spectrum parasite control should be instituted.”

Remember that once your cat is parasite-free she can still be re-infected with roundworms if she goes outside, has access to infected dirt, such as in a “catio,” or catches any prey animals.

Tapeworms

Tapeworms are the second most common parasite in cats. There are two types of tapeworms routinely seen in cats, with the most common tapeworm being Dipylidium caninum, seen in both dogs and cats. This tapeworm is usually ingested when a cat is grooming and accidentally ingests an infected flea, as passage through a flea is part of its normal life cycle.

What you may see are tiny pieces of debris that look like grains of rice around your cat’s rectum and tail or white, wiggly sacs of eggs called proglottids on the feces or around the rectal area. The proglottids are sections of the adult tapeworm that drop off with the eggs inside.

While most cats do not show any clinical illness from this tapeworm infection, it is certainly distressing to the family. Humans are rarely infected by accidentally ingesting an infected flea.

Praziquantel and epsiprantel are two medications that are commonly used to treat this parasite. It’s critical to understand that if you do not get rid of fleas, the tapeworms will likely return, so you must deal with them as well (more on fleas in an upcoming issue).

A second type of tapeworm that can be found in cats is called Taenia taeniaeformis. Cats acquire this tapeworm by catching and eating infected rodents. The same type of dried rice or wiggly white proglottid is seen on the rectal area or in the bedding of an infected cat.

Your veterinarian can examine the proglottid, or break it open to examine the eggs within to determine which type of tapeworm your cat has. The same drugs used for Dipylidium infections are effective for Taenia species infections. It helps to know which species of tapeworm an infected cat has, as this will inform other management practices, such as the institution of a flea-control program or restriction of outside access to prevent mouse hunting.

For more information visit www.vet.cornell.edu/fhc/Health_Information/brochure_parasite.cfm and www.petsandparasites.org/about-capc/, which includes prevalence maps for many parasites.