Researchers studying feline mammary cancer at Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine have set an ambitious agenda. They hope that their ongoing work will lead to better diagnosis, treatment and prevention of breast tumors in cats and humans. Much of their interest lies in how a novel class of drugs affects breast cell tumors.

In a study funded by the Cornell Feline Health Center, Assistant Professor Gerlinde Van de Walle, DVM, Ph.D., and Associate Professor Scott Coonrod, Ph.D., both working at the Baker Institute for Animal Health, have identified a promising chemical, BB-Cl-amidine, that seems to kill off feline mammary cancer cells while leaving healthy cells unaffected.

Malignant Tumors. The chemical inhibits certain enzymes, called peptidylarginine deiminase (PAD), which tend to be over expressed (increased) in feline mammary tumors. The majority of these tumors are malignant, and they’re the most frequently diagnosed cancer in female cats greater than 10 years of age. The cancer can also develop in younger cats and, in rare cases, male cats.

“If you can identify certain enzymes that are over- or under-expressed in tumors, those can be targets for the development of both diagnostics and treatments,” Dr. Van de Walle says. “These studies are all still in vitro (occurring in a laboratory setting), but the effects of the PAD inhibitors seem consistent and definitely have potential.”

Drs. Van de Walle and Coonrod have also undertaken related studies, funded by the Morris Animal Foundation, in which they are investigating a different enzyme, spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK), and its role in feline and human breast cancer. They found that the SYK gene is turned off in mammary cancer cells from cats as well as humans. If researchers can uncover why and how the gene is suppressed, they could devise a way to turn it back on.

Bigstock

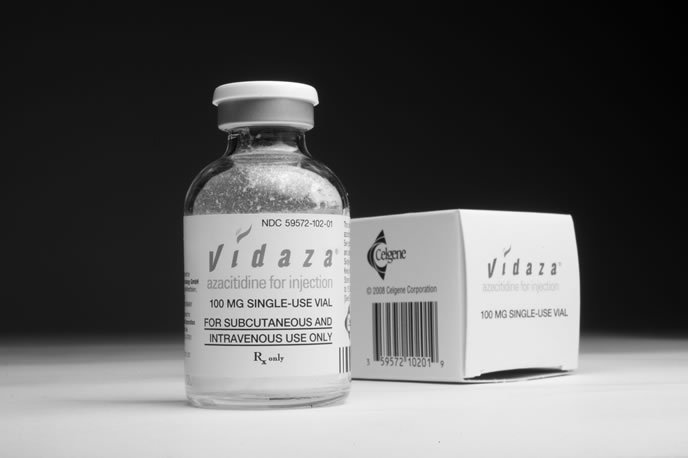

In this regard, Dr. Van de Walle evaluated the drug 5-Azacytidine, marketed under the name Vidaza and already used in the treatment of certain human cancers. It could successfully increase the expression of SYK in both feline and human mammary cancer cells, at least under laboratory conditions.

These studies and others across North America (see sidebar on Page 7) seek to better understand the underlying causes and indicators of breast cancer to apply the knowledge from one species to another. Such cross-species comparisons are possible because breast cancer occurs naturally in cats and is similar in some ways to the disease in humans.

An estimated 30 to 40 percent of cats are afflicted with cancer in their lifetimes, and nearly one-third of these cases involve malignancies in the mammary glands. More than 85 percent of feline mammary tumors are malignant. They’re very aggressive, easily spreading to surrounding tissue, lymph nodes and lungs.

Mike Connell

Mammary gland tumors are a diverse group of tumors with a wide range of biologic behaviors, says Cheryl Balkman, DVM, ACVIM, senior lecturer and Chief of Oncology at Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. That makes their diagnosis and treatment all the more challenging. “Researchers continue to work on classifying these tumors to better predict their behavior in the patient by investigating molecular profiles and receptor expression of these tumors, as is done in people,” she says. “But as of yet, there isn’t a commercial test available, and work continues.”

Better Prognosis. Like breast tumors in humans, feline mammary tumors start as small lumps beneath or next to a cat’s nipple. “The most important thing for owners to know is that pets have a better prognosis when the tumors are small — under two centimeters [less than an inch] in cats,” Dr. Balkman says. “It is important to for owners to take their pets to a veterinarian if they notice any lumps in the region of the mammary glands. It’s also important to have a veterinarian examine their pet every six to 12 months as they get older.”

Cornell

Owners can play a valuable role in early detection of mammary tumors by routinely screening for lumps on their pets’ undersides, particularly around the nipples. In some cases, cats might excessively lick or groom small mammary tumors, which can become infected and begin to emit a strong odor.

Often, cats with small tumors show no other symptoms of disease, but as the tumor grows and the malignancy spreads, general signs of poor health, like weight loss or lethargy, will become evident.

The underlying causes of feline mammary gland cancer are unknown.

Celgene

No External Links. While researchers like Drs. Van de Walle and Coonrod continue to try to better understand the genetic abnormalities that lead to various forms of cancer, no clear link has been established between known external cancer-causing agents — like environmental carcinogens and sunlight exposure — and mammary cancer in cats.

Breed, however, does seem to play a role. For unknown reasons, Siamese cats have twice the risk of mammary cancer as other breeds and tend to develop the disease earlier in life.

Hormones also seem to be a significant factor. Dr. Balkman notes that it is very rare for mammary gland tumors to develop in cats who have been spayed early in life, such as before the first heat cycle, which usually occurs around 6 months of age. “This is one of the best ways to prevent these tumors from developing,” she says. In fact, one study found that spaying a cat before 6 months of age reduced the risk of mammary cancer by 91 percent. Spaying before 1 year of age resulted in an 86 percent reduction.

When a small lump is identified, veterinarians typically use a fine-needle aspirate to determine if the mass is a mammary tumor. If cancer is suspected or confirmed, they might also perform a fine-needle aspirate of nearby lymph nodes to determine if the mass has spread. Because such tumors can spread to the lungs or other organs, chest X-rays are often taken to check for that possibility. Blood work might also be recommended as a health screen before anesthesia for surgery.

Treatment will depend on the size of the tumor, the extent to which it has spread and the cat’s overall health. If the tumor is confined to the mammary glands, a veterinarian will likely recommend removal of the tumor or even the entire breast (mastectomy).

“Because mammary tumors in cats are highly aggressive and have a high risk of metastasis, treatment with chemotherapy is often discussed to try to slow down the spread of the cancer,” Dr. Balkman says. “However, further studies are needed to determine the appropriate chemotherapy that can provide a strong survival advantage, as currently this data is limited.”

The expense of diagnosis and treatment related to mammary tumors varies with each patient. Evaluation typically costs $200 to $600, and the cost of surgery, depending on how extensive it needs to be to completely remove the tumor, ranges from $1,500 to $3,000 at Cornell.

As in humans, the prognosis for cats treated for mammary gland cancer depends heavily on how soon the disease is caught. The outlook is guarded for cats with large tumors with a high degree of malignancy, especially if the cancer has spread.

However, if treatment begins early, cats have a much better survival, which can range from one to four-and-a half years if the tumor is smaller than two centimeters in diameter. As research continues at Cornell and other institutions, new advanced diagnostics and treatments could be on the horizon to improve the outlook even further.