In a 2021 study published in Animals, a peer-reviewed open-access publication, researchers found that 58.2% of cats in rescue and 82.2 % of free-roaming outdoor cats were infected with intestinal parasites.

A 2020 retrospective analysis study published in Parasites and Vectors evaluated 1,272,460 fecal test results from cats in the United States and found that young kittens were more frequently infected with intestinal parasites than older adult cats and that areas in the western United States had lower parasite percentages than the rest of the country, except for Giardia, which is found pretty much everywhere.

As if that’s not enough, a 2019 study in Biology Letters considered the risk of intestinal parasites in indoor versus outdoor cats and found that outdoor cats are 2.77 times more likely to have intestinal parasites than indoor cats.

What Do The Results of These Studies Mean to Cat Owners?

If your cat goes outdoors, it is especially important for you to prevent, monitor for, and treat intestinal parasites.

If your cat is indoor only, the risk of a new intestinal parasite infection is low, but monitoring and appropriate treatment are prudent.

Anytime you get a new cat, it is important to check for and appropriately treat intestinal parasites and to make sure they are free of parasites before allowing them to share litterboxes with your current cats.

Why Do We Care?

Firstly, parasitic intestinal worms are gross, and no one wants to think about them, let alone see them, in their home. More importantly, they can deprive your cat of important nutrients, carry other diseases/parasites, and may contribute to chronic conditions like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

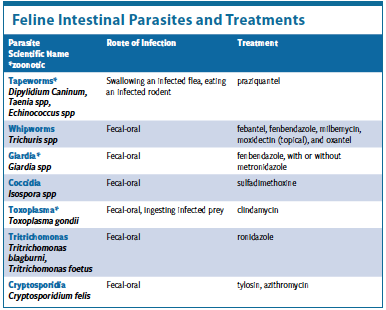

Finally, many of these parasites are zoonotic, meaning they are potentially contagious to people.

Many cats harboring intestinal parasites have no symptoms, which makes monitoring with periodic fecal tests even more important. Symptomatic cats may experience a combination of vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, poor hair coat, lethargy, and loss of appetite.

Many cats harboring intestinal parasites have no symptoms, which makes monitoring with periodic fecal tests even more important. Symptomatic cats may experience a combination of vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, poor hair coat, lethargy, and loss of appetite.

The most common intestinal worms of cats are roundworms (Toxocara cati, Toxocara leonina) and hookworms (Ancylostoma spp, Uncinaria stenocephala).

Kittens usually become infected with roundworms early in life while nursing, at which time roundworm larvae are passed from an infected queen’s mammary glands to the kittens who are nursing.

Kittens should be dewormed according to the strategic deworming recommendations for control of hookworms and roundworms from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American Association of Veterinary Parasitologists (AAVP). This entails proactively deworming (usually with the drugs pyrantel pamoate and possibly fenbendazole) all kittens four times between 2 and 9 weeks of age, even if fecal test results are negative.

Adopted cats with no history of prior deworming should be dewormed two to three times at two- to three-week intervals. Effective monitoring involves two to three repeat fecal tests throughout kittenhood, as eggs can be shed intermittently, resulting in false negative fecal exams.

Adult cats who test positive for roundworms or hookworms should be treated twice, three weeks apart, to eliminate all life stages of the parasite.

Adult cats who go outdoors should have fecal exams done twice annually and be proactively dewormed at least quarterly. If fecal exams are repeatedly positive, then monthly preventative deworming is recommended.

It is acceptable to simply monitor indoor cats with annual fecal exams, provided they were appropriately dewormed as kittens or new adult adoptees.

Intestinal parasites are common in cats, more common in cats that go outdoors, and some are potentially contagious to humans. Monitoring with periodic fecal exams is important for both indoor and outdoor cats. If helminth or protozoan parasites are identified by fecal exam, specific treatment should be administered. Proactive prevention should be considered for cats at highest risk. This can be accomplished with quarterly deworming for the most common intestinal parasites (roundworms, hookworms, and tapeworms) for cats that go outdoors.

Effective options for preventing all three of these parasites include topical Profender (emodepside and praziquantel) and oral Drontal (praziquantel and pyrantel pamoate).

Other preventatives that cover roundworms and hookworms, but not tapeworms, include the topicals Revolution (selamectin and sarolaner), Advantage Multi (imidacloprid and moxidectin), Bravecto Plus (fluralaner and moxidectin), and oral Interceptor (milbemycin). Oral Heartgard (ivermectin) prevents hookworms in cats but not roundworms or tapeworms