Bringing your cat to the veterinary hospital for a procedure under general anesthesia is never fun. It’s scary, and you leave hoping all goes well because no one can make any guarantees when it comes to anesthesia. Still, knowing what’s involved in the process may relieve your angst and uncertainty about your cat having surgery.

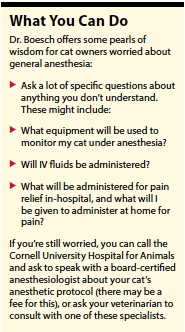

“The risk of serious injury or death is extremely low if anesthesia is performed properly,” says Dr. Jordyn Boesch, associate clinical professor, section of anesthesia and pain medicine, Cornell University’s College of Veterinary Medicine. “We prepare for every possible emergency situation, but some factors are out of our control. For instance, a patient may suffer an unexpected adverse event after administration of a drug, and despite being ready to treat said reaction, the patient might fail to respond.”

Young, healthy pets have the lowest risk. A preoperative health classification system created by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) for humans has been adapted for animals.

This system is frequently used by veterinarians to help determine a patient’s individual risk factors and to formulate a specific anesthetic plan geared toward minimizing that patient’s anesthetic risk. For example, the lowest risk is encountered in a young, healthy patient. The highest risk occurs in patients with advanced diseases like heart or kidney disease, and the surgical risk must be managed because the patient will not do well without surgery.

Managing a Cat Under Anesthesia

The big things your veterinarian and licensed veterinary technician (LVT) are monitoring and managing while your cat is under anesthesia are:

- Airway integrity

- Breathing and oxygen levels

- Heart rate and rhythm

- Blood pressure

- Body temperature

- Depth of anesthesia

There are many modern gadgets available to veterinarians for monitoring and managing anesthetized patients. These include continuous electrocardiography (ECG), digital respiratory and blood pressure monitors, oxygen and carbon dioxide level monitors, and intravenous (IV) pumps for metered fluid and drug administration. Gadgets that aid in maintaining normal body temperature include heated surgical tables, warm blankets, warm-water circulating pads, IV fluid warmers, and warmers for inhaled oxygen.

During a procedure requiring anesthesia, a well-trained, experienced LVT usually monitors the cat while the veterinarian performs the procedure. The LVT continually ensures that your cat remains properly under anesthesia, called “anesthetic depth,” and makes any necessary adjustments, with the veterinarian’s guidance. The LVT also monitors the cat’s body temperature, heating or cooling the cat as needed. In many veterinary hospitals, the same LVT remains dedicated to your cat’s care all the way through recovery until it’s time for the cat to go home.

Cats Present Unique Challenges

“Cats are not small dogs!” says Dr. Boesch. “They have a limited capacity to metabolize certain drugs compared to dogs. They develop adverse effects from some drugs more commonly than dogs; for instance, opioids can cause hyperthermia, or high body temperature. On the opposite side, because they are small, they are more prone to hypothermia, or low body temperature, during general anesthesia.”

The cat’s trachea, or “windpipe,” is tiny and easily damaged if not carefully managed. Endotracheal breathing tubes have air cuffs that are inflated to create a firm seal to prevent aspiration while under anesthesia. If this cuff is inadvertently overinflated, tracheal rupture can occur in cats. “Simply changing a cat’s body position during anesthesia without disconnecting the endotracheal tube from the anesthesia machine can damage the trachea,” says Dr. Boesch.

IV fluid administration is more difficult with cats than dogs. IV fluids are given during anesthesia to help maintain blood pressure. Because cats are so tiny and their blood volume so small, overzealous administration of IV fluids can overwhelm the heart and lungs, resulting in fluid congestion in the lungs.

Having a well-trained, experienced LVT dedicated to your cat obviously minimizes most of these concerns; but they are real, especially in cats.

Prior to Anesthesia

Many hospitals ask you to bring your cat in for preanesthetic bloodwork prior to the day of the procedure. At this time, they will assess the cat for any issues that should be addressed prior to surgery and assess the cat’s stress level. Because stress wreaks havoc on blood pressure and heart rate, pre-medications meant to minimize stress, among other things, will often be dispensed at this visit.

This cat is receiving pre-oxygenation via face mask and propofol intravenously to softly induce anesthesia.

“Anesthesia begins at home,” says Dr. Boesch. “I recommend that veterinarians send home certain drugs with owners to be given the night before to prepare their cat for admission the next morning. An anti-emetic, or anti-nausea drug is important, as many cats are nauseated by car rides and by anesthetic drugs. A sedative like gabapentin will relax a nervous cat for the car ride and admission to the hospital, both of which can be extremely stressful. Neither of these drugs will interfere with the anesthetic protocol nor with the procedure to be performed and can really change a cat’s veterinary experience for the better.”

Dr. Boesch advises that every cat should have at least some bloodwork performed before anesthesia. “Even in young, apparently healthy cats, we check to make sure they aren’t anemic, have normal concentrations of protein and glucose in their bloodstream, and normal kidneys,” she says.

“As cats age,” says Dr. Boesch, “the risk of various diseases becomes greater, so we perform more comprehensive bloodwork after about the age of 7 or so to evaluate their kidneys, liver, and many other variables in greater detail.” Older cats should have thyroid levels checked prior to anesthesia, and cats with heart murmurs should have additional diagnostics performed like chest x-ray, ECG, and/or an echocardiogram prior to considering anesthesia.

On the Day of the Procedure

Once the cat has been admitted to the hospital, the veterinarian performs a preanesthetic physical exam, making sure that all is well prior to inducing anesthesia. An anesthetic plan including dosages will be made, and drug dosages for emergency intervention, should it become necessary, will be calculated in advance and kept at hand.

The LVT will place an intravenous catheter. This allows fluid support to be administered during the procedure, which helps maintain blood pressure. It also allows quick, easy access for administration of drugs, which is especially important should the cat require emergency treatment while under anesthesia. Injectable medications will be administered for sedation and preemptive pain management.

When it’s time for the procedure, the cat receives pre-oxygenation via face mask and a short-acting anesthetic drug like propofol intravenously to softly induce anesthesia (unconsciousness). Next, an endotracheal tube will be placed, and an inhalant gas anesthetic like isoflurane or sevoflurane will be administered. Inhalant anesthetics are most frequently used for maintenance of anesthesia during procedures, as they can be adjusted to the lowest dose necessary to maintain unconsciousness.

After the Procedure

Once the procedure is complete, whether it be surgery, dentistry, radiation therapy, or advanced imaging like CT or MRI, the cat will be allowed to wake up while still intubated. Intubation refers to the breathing tube that was inserted so the cat can breathe while anesthetized.

Once it is determined by the veterinary staff that the cat is awake enough to swallow and thereby naturally protect its own airway, the endotracheal tube will be removed. Your cat will be moved to a recovery area, where he or she will continue to be carefully monitored by your LVT until fully awake and ready to go home.

Post-operative pain management is an important aspect of any potentially painful procedure. “After anesthesia,” says Dr. Boesch, “if the cat is stable, we will administer an anti-inflammatory drug for pain relief, and possibly more opioids. All cats should go home with at least three days of an analgesic drug after a painful procedure like spay, neuter, tooth extraction, etc.” If you aren’t given one, Dr. Boesch suggests asking for it.

Post-operative pain management is an important aspect of any potentially painful procedure. “After anesthesia,” says Dr. Boesch, “if the cat is stable, we will administer an anti-inflammatory drug for pain relief, and possibly more opioids. All cats should go home with at least three days of an analgesic drug after a painful procedure like spay, neuter, tooth extraction, etc.” If you aren’t given one, Dr. Boesch suggests asking for it.

Is It Worth It?

While there is always risk associated with anesthesia, thanks to modern day medicine and advanced technology, that risk can be minimized.

A good model to use when deciding whether it’s worth the risk to have your cat undergo anesthesia for a procedure is the risk:benefit ratio. If the benefit of the procedure for your cat outweighs the perceived risk, then the answer is yes. But, if the risk of anesthesia for your cat, based on your cat’s unique health status, outweighs the benefit of the procedure, you might want to rethink things. In these cases, discuss an alternative plan with your veterinarian.

Some cases are easy to determine that the benefit outweighs the risk:

- An 8-month-old apparently healthy female kitten for spay

- A 5-year-old otherwise healthy cat with severe, chronic, painful dental disease for dental work

- A queen having difficulty or inability to birth kittens, because without surgery mom and babies may die

- A young, otherwise healthy cat with intestinal blockage for abdominal surgery

Cases in which the risk may be higher than the benefit include a geriatric cat with untreated hyperthyroidism and a non-painful mouth in for a routine dental cleaning or a senior cat with heart disease going under full anesthesia for a grooming procedure.

There will always be scenarios in which the decision making is less clear cut. These more difficult cases require in-depth conversation with your trusted veterinarian.ν

Eileen Fatcheric DVM

Veterinary anesthesia is similar to human surgery, with constant surveillance.

Jordyn Boesch, DVM, PhD, DACVAA, focuses her research on pain and its management. Her interest in anesthesia and pain management applies to all species.