I

f your cat has sudden changes in behavior like excessive yowling or unusual hiding, or if you notice her bumping into things or stumbling uncharacteristically, take a close look at her eyes. Do you see the normal vertical slit-like pupils you’re used to seeing, or are the pupils huge and round (dilated)? Wave your fingers toward her face. If she doesn’t blink or flinch, especially if her pupils are dilated, your cat is likely suffering from acute blindness.

Many things can cause blindness in cats, including cataracts, glaucoma, brain disease/tumors, and even low blood sugar episodes in diabetic cats. But the most common cause of blindness in cats is retinal disease, and retinal damage due to high blood pressure (hypertensive retinopathy) is the most common.

Retinal Damage

If caught and treated early enough, blindness due to retinal detachment may be reversible. “Cats with retinal detachment from hypertension can regain vision if the retina reattaches and does not subsequently degenerate,” says Dr. Kelly Knickelbein, board-certified veterinary ophthalmologist and assistant professor of opthalmology at Cornell University’s College of Veterinary Medicine. “Sadly, some of them regain vision with reattachment but go on to have retinal degeneration that leads to irreversible blindness.” Clearly, this is a condition better prevented than treated.

Treatment of hypertensive retinopathy involves oral medication to lower systemic blood pressure. Blood pressure will be monitored weekly until it is within the normal range, and therapy is typically for life. If your cat is diagnosed with high blood pressure, she should be tested for thyroid and kidney disease, with therapy instituted or adjusted as indicated. Managing the underlying diseases makes managing the associated hypertension easier.

Acute blindness due to hypertension is an emergency. With quick diagnosis and treatment, some cats will regain or retain at least some vision, which dramatically improves overall quality of life. The best way to avoid this sad situation is to have your senior cat examined twice a year, have blood work done at least once a year, and ask for blood pressure measurement at each visit.

Hypertension

Hypertension, or high blood pressure, occurs most commonly in older cats suffering from hyperthyroidism and/or chronic kidney disease (CKD), however, it can be idiopathic, which means the cause is unknown. Since many cats show no outward signs of hypertension early in the disease process, veterinary consultation is essential.

Untreated hypertension can cause damage not only to the eyes, but also to the heart, brain, and kidneys. Blindness due to hypertension is the result of tiny vessels bursting within and behind the retinas. These burst vessels cause hemorrhage in the eyes that damages the retinas and ultimately causes them to detach. Hypertensive retinopathy (detachment) almost always affects both eyes, rendering most affected cats completely blind.

Less Common Causes

Retinal Degeneration. Retinal degeneration often happens in the aftermath of retinal detachment regardless of cause. Vehicular trauma, blunt force trauma, and falls can cause partial or full retinal detachment. These cats may initially remain visual, at least enough to navigate without trouble, but may suffer progressive loss of vision. The progression can be so subtle that pet owners may not even pick up on it until total vision loss occurs. There is no treatment for this form of retinal disease.

Taurine deficiency. Taurine is an essential amino acid for cats, which means they cannot make this amino acid and must get it from their diet. Taurine-deficient diets are known to cause heart disease (dilated cardiomyopathy) and retinal degeneration in cats. If your cat is eating commercial cat food that has an AAFCO Statement of Nutritional Adequacy on the label, there is no need to worry. Stray cats eating nutritionally incomplete diets are obviously at risk, as are cats being fed home-cooked meals not appropriately supplemented with taurine. If you home cook for your cats, be sure to work with a veterinary nutritionist to ensure the diet is nutritionally balanced and complete.

Baytril side effect. Enrofloxacin, an antibiotic commercially known as Baytril, was associated with sudden blindness in cats when it first became available. This toxicity resulted in retinal damage and permanent blindness. The potential for retinal toxicity with Baytril was eventually determined to be dose-dependent.

“Enrofloxacin-induced retinal degeneration is definitely still a thing in cats,” says Dr. Knickelbein. “Rather than idiosyncratic (meaning no rhyme or reason to which cats might be affected), retinal degeneration can be expected in all cats that receive high dosages of enrofloxacin. The labeled dose of 5 mg/kg once daily is the absolute maximum that should ever be used, and in my experience most veterinarians avoid use of enrofloxacin in cats to avoid the potential for this devastating toxicity.”

It’s scary, given that the damage is permanent. If enrofloxacin is prescribed for your cat, it might be worth asking if there are alternative medications for the condition being treated.

Genetics. Progressive Retinal Atrophy (PRA) is a genetic disorder that leads to blindness in affected cats. It is most common in Persians, Himalayans, and Exotic Shorthairs. It has also been seen in Abyssinians, Siamese, and other breeds. Vision issues may be seen in young kittens but may not become apparent until adulthood. The best way to avoid this situation is to have breeding stock DNA tested for the gene mutation and to avoid breeding affected individuals. If you are purchasing one of these purebred cats, ask for documentation of negative tests in the sire and dam.

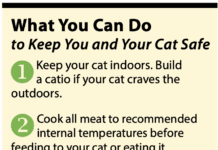

Blind cats can still enjoy their lives. They must stay indoors to remain safe. They usually learn to navigate well as long as things in their environment are kept consistent. Still, prevention is key. Be proactive. Feed your cat properly. Screen your older cats for hyperthyroidism, kidney disease, and hypertension; and do everything you can to protect your cats from trauma.

Kelly Knickelbein, VMD, is a board-certified veterinary ophthalmologist and assistant professor of ophthalmology at the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine.