In a normal kitten, there is a solid tissue barrier between the nose and the mouth. During development, these tissues grow from the sides of the common oral and nasal cavity and meet in the middle, forming the roof of the mouth, called the palate. The palate is comprised of hard (front portion) and soft (rear portion) regions.

If these tissues fail to grow together normally before a kitten is born, the kitten will have a cleft palate. This can be a small defect—such as a tiny hole in the hard palate—or a split that runs from the lips all the way back through the soft palate. A major or primary cleft is obvious right away because the affected lip is split. Sometimes it is just the lips that are split, but often the damage is more extensive.

When you check inside the mouth of a kitten with a cleft palate, you can often see the split going back along the top of the oral cavity. Small or secondary clefts may be harder to visualize, especially in a wiggly kitten.

Signs of a Cleft Palate

An affected kitten might lag behind her littermates in growth. You might notice milk draining out of the kitten’s nose during or after nursing. The kitten may cough, sneeze, or have trouble nursing.

Some cleft palates escape notice until a kitten is eating solid food and lapping food up. If milk or food is inhaled, the kitten will likely develop aspiration pneumonia, which can cause significant illness and even death.

Kittens with a cleft palate do best with a feeding tube until treatment can be attempted. That may mean separation from the queen much of the time, but the use of a feeding tube can help to prevent aspiration pneumonia.

Affected kittens are generally diagnosed on their initial kitten physical exams. Clinical signs may tip off a knowledgeable breeder to check the litter. Rescues and shelters that deal with large numbers of kittens often quickly identify these defects as well.

Causes

A genetic predisposition for cleft palates is suspected in some cat breeds, including Persians, Ragdolls, Siamese, Savannahs, Ocicats, and Norwegian Forest Cats. Female kittens are at higher risk than male kittens.

Other causes include:

- Illness in the queen during pregnancy

- Too much vitamin A or vitamin D in the queen’s diet

- Exposure of a pregnant queen to certain medications, including corticosteroids and some antifungals

Treatment

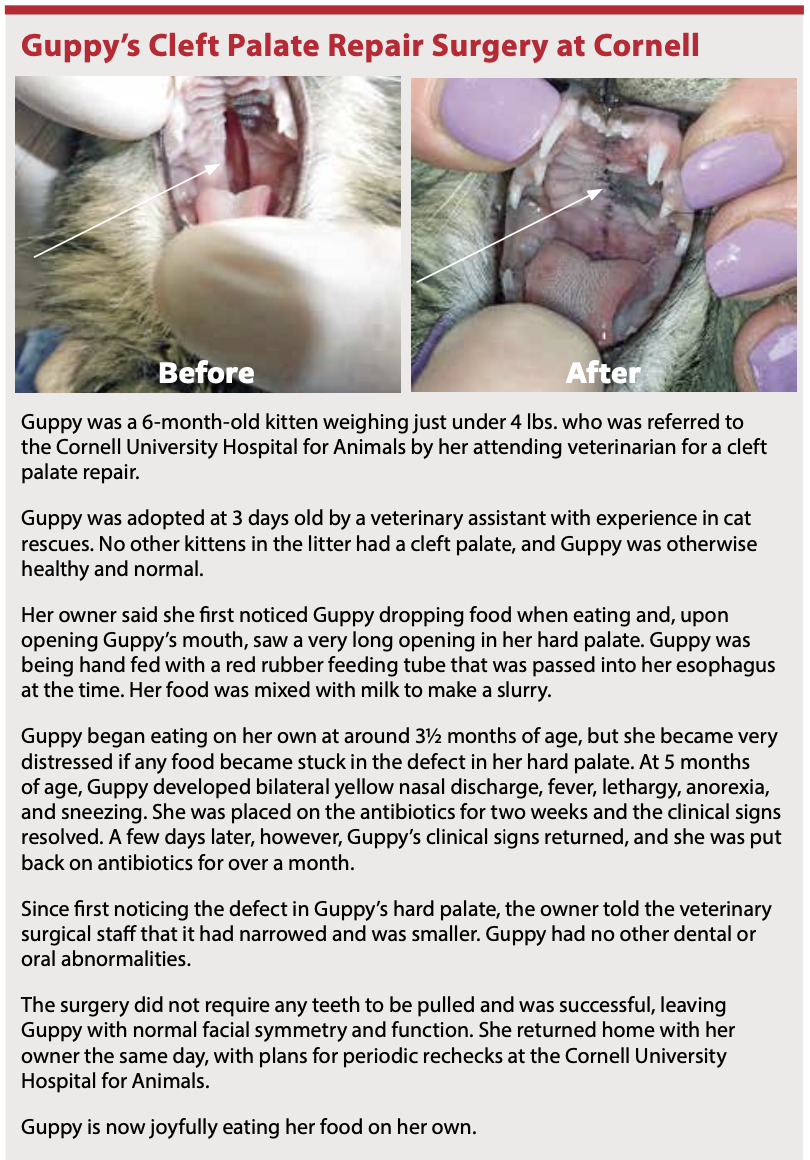

Using a feeding tube and preventing the affected kitten from eating or drinking on his own until 3 to 4 months of age minimally (sometimes as long as 6 months of age) is best, according to the American College of Veterinary Surgeons.

Some defects will heal a bit on their own, but rarely to the extent that the defect disappears.

Some defects will heal a bit on their own, but rarely to the extent that the defect disappears.

Surgery is the definitive treatment for a cleft palate. Waiting until an affected kitten has grown a bit before surgery is often recommended, and most kittens will require more than one surgery to completely fix the defect.

The first surgery often removes teeth to help free up tissue to make it available to cover the defect. The second surgery is usually the actual repair. Corrective surgery for cleft palates is best referred to a board-certified veterinary surgeon.

Surgeons have had to be creative at times in fixing these defects, and complications are not unusual. Owners should be prepared for possible setbacks and long-term nursing care until healing is complete. Sadly, euthanasia is often chosen when a large defect is identified.

Postoperative care is intensive for three to four weeks, with tube feedings continuing, antibiotics often being prescribed, and Elizabethan collars necessary to prevent any rubbing. The kitten’s activity will need to be closely monitored. No chewing, tugging on anything, or rubbing her face should be allowed.