While chronic kidney disease (CKD) cannot be cured, it can often be managed for many years. As with most diseases, early diagnosis and proper management improves the long-term prognosis for your cat.

Early Clinical Signs

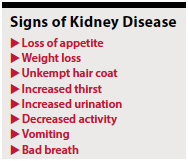

Between 30% and 40% of cats over the age of 10 will have some evidence of CKD. Despite this high prevalence, many owners miss CKD’s early signs because they are usually subtle and nonspecific.

“I think many cat owners miss the early signs because those signs are usually so insidious,” says Noelle Perry, DVM (Cornell 1996). “That is why screening diagnostics like blood and urine tests are so important.” Dr. Perry says that most of her clients who own cats with CKD report an increase in wet spots in the litterbox and/or increased drinking to a level that seems unusual.

To increase your chance of catching kidney failure early, consider using water bowls that allow you to accurately assess water intake. You might choose a bowl with stripes or a design that offers an instant visual “gauge” so you can judge water consumption. Some cat bowls offer measuring lines that can be used to measure the volume of water consumed. Otherwise, when you change the water bowl daily—you do change the water every day, right?—you can use a measuring cup to measure its contents and keep a log for comparison.

If you use a water fountain, which is preferred by many cats, it is more difficult to judge water volumes with just a glance, but you can use the measuring-cup method with your daily change of water, too.

Monitoring food consumption is also important in identifying a lack of appetite promptly. This can be especially difficult if you have a multi-cat household. Consider feeding affected cats in a separate room or using an automated feeder if this is the case. As with water consumption, keeping a log for comparison over time can be helpful.

Of course, all litterboxes should be cleaned daily, and you should be able to tell if the box is wetter than normal. With a multiple cat household, the problem is determining who is producing more urine if you do notice an increased wetness in the litter. The best way to do this is to isolate the cats and give each their own litterbox. Some people will isolate one cat at a time to save on rooms and litterboxes.

Of course, all litterboxes should be cleaned daily, and you should be able to tell if the box is wetter than normal. With a multiple cat household, the problem is determining who is producing more urine if you do notice an increased wetness in the litter. The best way to do this is to isolate the cats and give each their own litterbox. Some people will isolate one cat at a time to save on rooms and litterboxes.

Some cats with CKD will vomit or have unusually bad breath, but these signs are not as common as the others listed above and usually occur in cats with more advanced disease.

Time for a Diagnosis

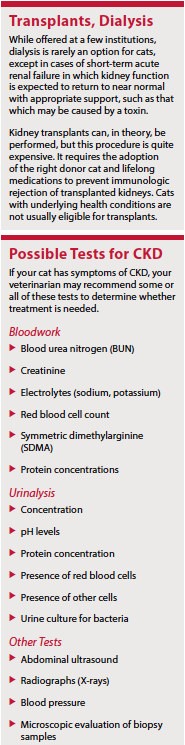

Over the years, advances have been made in diagnosing CKD in cats. Your veterinarian will take a thorough history and do a complete physical exam, including bloodwork and a urinalysis.

A basic urinalysis may show some changes indicative of an early kidney problem. Urine specific gravity, which tells how well your cat concentrates her urine, can be a clue, as can evaluating protein in the urine. An inability to concentrate urine and/or loss of protein into the urine can be indicators of CKD. If protein is detected in your cat’s urine, your veterinarian may suggest measuring the creatinine ratio. Creatinine is a waste product that is normally filtered from the blood by the kidneys, and it may accumulate in the blood when kidneys are not functioning appropriately.

Excess protein in the urine may be caused by things other than CKD. For example, microscopic blood and white blood cells found with urinary tract infections can result in excess urinary protein. Finally, urine samples can be contaminated by proteins found in the environment and/or the external genitalia if the sample is obtained by a free catch or is collected from a clean litterbox that has no litter in it.

A standard blood panel usually will show some changes if your cat has CKD. Among the first values to change are creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN), another waste product of protein metabolism. The BUN and creatinine increase when the kidneys lose the ability to filter these metabolites out of the blood. Dehydrated cats may also show increased creatinine.

SDMA, or symmetric dimethylarginine, is an amino acid that is routinely broken down in your cat’s body and eliminated via the kidneys. SDMA is a sensitive indicator of renal function, as levels may rise with 40% loss of renal function. In comparison, as much as 70% of the normal kidney function has been lost by the time levels of BUN and creatinine rise. Some blood chemistry panels for senior cats now include SDMA as part of the panel, but others do not.

Treatment Plans

Renal health professionals at the International Renal Interest Society (IRIS) developed a staging scheme that includes four stages of kidney failure to help evaluate cats.

A primary factor in classifying a cat’s CKD is bloodwork, including creatinine and SDMA concentrations. Additional factors include protein loss in the urine and blood pressure, as the kidneys are vital to the maintenance of normal blood pressure. Cats with CKD may develop high blood pressure.

IRIS emphasizes considering two primary objectives when planning a treatment regimen for cats with CKD: maintaining good quality of life and slowing the progression of the disease.

Encouraging water intake is vital. Place multiple bowls of fresh, cool water in easy-access spots around the house. You can add some water to your cat’s food or switch from dry to canned food. If your cat isn’t impressed with water on her food, try adding either a small amount of water from a can of tuna or low-sodium chicken broth to her water, as these may entice picky cats to drink. For some cats, a dripping faucet or a pet fountain gets them drinking more.

Cats who are resistant to drinking more or who get dehydrated for any reason may need supplemental intravenous (IV) fluids at the veterinary clinic or subcutaneous (SC, under the skin) fluids at home. Most cats tolerate SC, and most owners can be taught to administer SC fluids.

Your veterinarian will likely recommend a prescription renal diet that has lower protein and phosphorus levels than regular cat food. If this is the case, introduce the diet change gradually, i.e.: 75% old diet, 25% new diet for four days, then 50/50 for four days, then 25/75 for four days. At that point, switch to 100% of the new diet.

If your cat objects, try another brand. Many brands and flavors are available in both wet and dry food, and most cats will eat at least one of these. If not, a veterinary nutritionist can assist with designing an appropriate homemade diet for your kitty.

Hypertension

Increased blood pressure is a common side effect of kidney disease. Any cat with CKD

A pet water fountain can encourage some cats to consume more water.

should have their blood pressure checked every three months, as uncontrolled hypertension can damage her heart, eyes, and brain, and can also worsen kidney function.

Medications that can be used to control hypertension in cats include a calcium channel blocker like amlodipine or an angiotensin receptor blocker like telmisartan. Luckily, these are both only given once a day, although some cats may require both.

Electrolyte Balance

Since the kidneys help maintain normal electrolyte balance, cats with CKD may have abnormal blood electrolyte concentrations. These can usually be managed via diet, but some affected cats may need phosphate binders, supplemental potassium, or other therapies to restore normal blood electrolyte concentrations.

The kidneys normally produce erythropoietin, a hormone that increases red blood cell (RBC) production, so a cat with CKD may have low levels of this hormone, which can cause him to become anemic because he’s not producing enough red blood cells. He may need transfusions or erythropoietin administration to restore RBC levels.

Prognosis

CKD is a progressive disease. While early diagnosis and treatment can slow the progression and improve a cat’s quality of life, there is no cure.

The prognosis for cats with CKD depends upon the IRIS stage at the time of diagnosis. Cats in IRIS stage 2, for example, have a median survival time of 15 months to three years. Cats in IRIS stage 4 at the time of their diagnosis have a median survival time of between 20 days and a little over three months.

In many, if not most cases, cats with CKD are humanely euthanized once their quality of life diminishes significantly. Your veterinary professional team is vital in providing support and guidance to owners of cats with CKD during the difficult time that they are considering this option.