It’s no secret that bladder issues are common in cats. Just walk down the cat food aisle and note all the diets touting “urinary tract health.” What may surprise you, however, is that what your cat eats is no longer considered the main culprit for the most common cause of lower urinary tract disease in cats. Dietary management is still important, mind you, but it has been one-upped by our favorite feline nemesis: stress.

Feline idiopathic cystitis (FIC) is the most common cause of lower urinary tract disease in cats, especially young to middle-aged cats. Studies have shown that greater than 50% of all feline bladder issues are due to FIC.

To understand it better, let’s break down the terms in FIC:

- “idiopathic” means we don’t know what causes it

- “cyst” refers to the bladder

- “itis” means inflammation

So, FIC is an inflammatory bladder disease without a known cause. That said, it’s becoming abundantly clear that stress plays a major role.

Even if your cat doesn’t appear outwardly stressed, hidden physiologic stress could be causing FIC. Research shows that some cats are genetically wired differently when it comes to responding to and managing stress.

Feline stressors include physical issues like pain and illness, as well as environmental stressors like moving to a new home or introduction of a new pet. Indoor confinement, even if your cat acts like the happy queen of the roost, is stressful.

The nervous systems of cats with FIC seem to be super-charged, with exaggerated physiological responses to stimuli that create normal, tempered responses in other cats. The result is a snowballing of the negative effects of stress in FIC cats.

Signs of Illness

Abnormalities of the bladder wall in FIC cats have been identified. These compromised areas allow urine to contact the sensitive nerve tissue underlying the protective mucosal lining of the bladder. Urine is irritating to this tissue, which is already highly sensitive in these cats. Progressive inflammation, worsening pain, and overreaction to that pain all lead to a hot mess in a hurry.

Signs of FIC are similar to the signs of many other lower urinary tract diseases in cats. These include:

- bloody urine (hematuria)

- straining to urinate (stranguria)

- urinating small amounts frequently (pollakiuria)

- painful urination (dysuria)

- abdominal pain

- licking at the genitals or lower abdomen

- urinating outside of the litterbox

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of FIC requires ruling out other potential causes of lower urinary tract diseases,

Litterbox problems should be promptly brought to your veterinarian’s attention.

including bladder stones, bladder tumors, and bladder infection. Testing usually includes urinalysis, urine culture, abdominal x-rays, and/or abdominal ultrasound. Once bladder stones, tumors, and infection have been ruled out, a presumptive diagnosis of FIC is usually made.

Treatment

Short-term treatment of an acute episode of FIC is focused heavily on pain management. Opioid medications like buprenorphine or tramadol are frequently prescribed.

Gabapentin, a popular neuropathic pain reliever, can be a big help. Sometimes, anti-spasmodic medications are prescribed, especially for male cats who are prone to urinary tract obstruction. Maropitant (Cerenia), an anti-vomiting medication, may be recommended, as it has anti-inflammatory and pain-relieving effects on internal organs.

Veterinarians commonly treat cats with urinary tract infections with antibiotics, which makes sense. If your cat is having recurring bouts of lower urinary tract signs, though, you and your veterinarian may want to reconsider the cause. An episode of FIC typically self-resolves without treatment in two to seven days. So, unless your cat has a positive urine culture or urinalysis findings that confirm a bacterial urinary tract infection, antibiotics may not be appropriate therapy. Your cat may get better without them.

Bottom Line

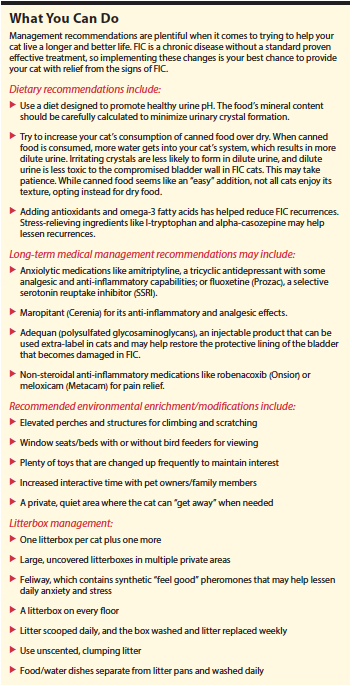

FIC is typically a chronic, recurring disease, and prevention is key to success. That means working with your veterinarian to develop nutritional, medical, and environmental management tactics (see “What You Can Do”).