215

“The linear accelerator is coming!”

“No, the linac is here and its almost ready!”

From my post in the Cornell Feline Health Center, in the middle of the universitys College of Veterinary Medicine, I could sense the anticipation. Veterinary professors arent normally an excitable bunch, and I guessed the linear accelerator wasnt a new sports car. So, I wrangled an invitation to visit the thing, and now the not-so-easily-impressed Dr. Mew is excited too.

What it is, this linear accelerator, is nothing less than the latest, most precise and effective machine for zapping cancerous tumors with radiation. And while cancer treatment of any kind is never a picnic, radiotherapy with this machine, and the professionals who run it, should give any pet confidence that the job will be done right and safely the first time.

My guide through a facility that makes the Starship Enterprise look like a Model T was Margaret McEntee, DVM, and the Cornell specialist in medical and radiation oncology made me feel at home. Cats are our favorite patients, she said, because you tolerate radiation therapy better than dogs or even humans.

Just visiting, I reminded her and asked for the specs. A hot rod like this should accelerate from zero to 60 in five seconds, I figured. Wrong again, Catman. What accelerates are trillions of electrons, speeded up to high-energy levels by electromagnetic waves. The high-energy electron beam itself can be used to treat superficial tumors. Or it can be made to strike a metal target and produce x-rays for treating more deeply seated tumors.

The head of the machine does move slowly and deliberately as it circles the patient and focuses the x-ray beam at the tumor from several different directions. In particular, this new machine at Cornell is a Siemens PRIMUS 6MV Linear Accelerator, and the number means 6 million electron volts – more than enough to make this cats hair stand on end. Lower energy levels can be selected to give the oncologists flexibility to treat various kinds of tumors in different patients.

Some assembly required

If you want a PRIMUS 6MV of your very own, it will set you back a cool $1.5 million for the machine, installation, and calibration by a medical physicist – not to mention structural renovations like 2.5-inch-thick interlocking lead bricks for shielding in concrete walls that are already several feet thick, chilled-water plumbing to cool the machine, and a big electrical service line to juice it up. Youll also need all the services of an operating room (anesthesia gas, oxygen, heart monitors, and more) plus closed circuit video so the linac operators dont have to be in the same room with the patient when the radiation beam is on.

The reason the operators use remote control is that stray radiation can be hazardous to their health. Rather, they get the anesthesia and monitoring systems started and cradle the patient in a custom-fitted Vac-Lok positioner (it looks like a

bed for astronaut cats, and you can take the positioner home, after the treatments). Then they check that lasers from the walls and ceiling are all pointed at a mark on the patient (so the computer-controlled linac and treatment couch are precisely positioned), and then retreat behind those thick walls to turn on the beam and treat the cancer. A lighted sign, X-ray in Use, and a beeping sound warn that the linear accelerator is running.

After about two minutes of treatment, the operators return to the linear accelerator and move the patient, who wakes up in a recovery room. Treatments continue five days a week, over three to four weeks, for 16 to 19 treatments. Some pets go home each day, if their humans live nearby, while others stay the week at the hospital and go home on weekends. Sometimes humans who live a greater distance away take vacation time and camp nearby in recreational vehicles while their pets are in treatment, McEntee told me.

White badge of courage

Radiotherapy patients do get one other souvenir, she said – a badge of courage, really: Fur that is lost in the spots where the x-ray beam has focused regrows in a completely different color. So, a mostly black cat like me might bear white patches of fur for the rest of its life. Otherwise, any sun-burn effect on the shaved skin usually disappears within a month, McEntee noted, while other side effects can occur, depending on the site that is irradiated.

288

As you can imagine, sophisticated, life-saving care like this is isnt cheap – around $4,000 for all the treatments and materials, tests and exams, including one or more CT (computed tomography) scans, and even more if surgery is needed to remove tumors. No, the veterinary oncologists are not trying to pay off a pricey machine in a hurry. In fact, Cornells linear accelerator was a gift, in part, from the Kresge Foundation, and the Feline Health Center chipped in, too. All the fees (which are far less than human patients pay for similar treatments) go for the specialized care.

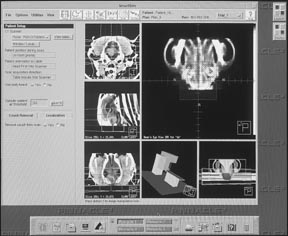

For example, simply devising the treatment plan can take up to three hours for one patient, McEntee explained. Starting with the CT scan (those slice by slice 3-D pictures that show exactly where the tumor is located and what its shaped like, in relation to vital organs that the x-ray beams must avoid) oncologists and their computer programs determine how much radiation – in what shape, intensity, and

time duration – should be beamed at the tumor.

We evaluate all alternative strategies in order to have the least possible effect on healthy tissue in organ systems while delivering the total treatment dosage over the safest, shortest time, McEntee assured me.

Shrinking the tumor

Sometimes the tumor gets smaller during the treatment process and other times it takes longer, she said, explaining why additional CT scans may be needed. It is not uncommon for it to take several months to see maximum reduction in the tumor after the end of therapy.

External beam radiation therapy with a linear accelerator is not the only kind of radiotherapy available at major veterinary clinics like Cornells. Radioactive iodine has been used for years for hyperthyroid conditions, and strontium-90 is used in

surface therapy for skin tumors, I learned. But for zapping tumors deep inside the body, theres nothing like a linear accelerator.

Because of the high costs and possible stresses on the animal patients veterinarians who refer cases to major centers, such as Cornell, like to counsel the pet owners and help them consider all pros and cons, including the pets life expectancy and predicted quality of life. Its always a tough call, and sometimes pet owners decide to let the cancer run its course.

As I left the linac, I remembered something Professor Rod Page, DVM, the director of the Comparative Cancer Program at Cornell, had told me: Fifty percent of cats and dogs over 10 years of age will experience cancer at some time in their later years. Im 12, and I hope to be one of the lucky ones. Just in case, I left a trail of kitty treats leading back to the linear accelerator. That big beam could be a lifesaver.