When the topic of intestinal parasites comes up, people immediately think of worms, such as roundworms (ascarids) and tapeworms. However, other parasites may be more common and equally debilitating for your cat.

Coccidia

Coccidial infections are extremely common in cats, especially kittens. These are Cystosiospora—also called Isospora species. Coccidia are microscopic protozoa. Luckily, coccidia tend to be species-specific, so feline coccidia won’t infect dogs or people.

Oocysts (eggs) are passed in the stool and then develop into the infective stage—sporulated oocysts. These sporulated oocysts are tough—they can survive for up to a year if environmental conditions are right.

Most cats are exposed to coccidia through environmental contamination, such as walking through contaminated soil and then grooming their feet. They can also acquire them by eating transport hosts, such as mice. The Cornell Feline Health Center says that cats who eat flies and other bugs may get infected that way, too, if the insects have oocysts on their bodies.

Meet T. foetus

This little guy can be difficult to distinguish from giardia

There is a “new kid” on the block when it comes to feline protozoa. Tritrichomonasfoetus, also known as T.foetus or T.blagburni, is a source of chronic diarrhea, especially in kittens and cats under two years of age. It can be difficult to distinguish giardia and T.foetus under the microscope without experience in evaluating motile protozoa. T.foetus is not affected by the usual giardia treatment drug, metronidazole, but requires ronidazole for therapy.

Kittens are the most likely to show clinical signs of illness with coccidial infections. You may notice your kitten has diarrhea with a lot of mucus, vomiting, and a lack of appetite. Dehydration and weight loss may follow. The diarrhea may be bloody, and severe cases can lead to death. Dehydration is especially dangerous for kittens and for stressed adult cats.

With age, most cats develop some degree of immunity against these parasites. Cats living in crowded conditions, such as shelters or group housing, may be predisposed to coccidia infection, both due to stress and the difficulty in keeping the premises free of infective oocysts.

A diagnosis of coccidiosis is achieved via a fecal flotation. It is important to identify the coccidial species. For example, Eimeria oocysts (a rabbit parasite) can mimic Isospora, but do not cause any clinical illness in felines. A cat may acquire Eimeria by hunting and eating rabbits and will pass Eimeria in the stool, but the cat will usually not be clinically affected.

Once coccidiosis is confirmed, cats should receive treatment. Sulfadimethoxine is currently the only drug FDA-approved for treatment of coccidiosis in cats, but veterinarians have used other medications successfully, including trimethoprim sulfonimide. It is important to follow up a diagnosis of coccidiosis with good hygiene and disinfection to remove or destroy any sporulated oocysts in the environment. Recheck fecals should be performed to confirm that the treatment has been effective.

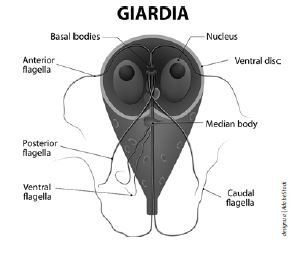

Giardia

Giardia are protozoal parasites that can infect many species, though certain types are species specific. These one-celled organisms have a flagella (a microscopic thin appendage) on one end that moves them around. They are best seen microscopically with a fresh fecal sample. An Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) test can identify antibodies to giardia, verifying an infestation. Cysts are not shed continuously, so testing samples obtained over a couple of days may be required.

Cats becomeinfested with giardia by eating or drinking cysts that pass through the feces and contaminate food or water sources, or by grooming after picking up cysts on their feet or hair coat. Like coccidia, giardia oocysts are tough—not killed by freezing or even the chlorination carried out by municipal water-treatment plants, as reported by the Cornell Feline Health Center. You may notice diarrhea in your cat, often with pale, “slimy” stools that have a bad odor. Foul gas may be passed, and over time, you may notice weight loss in your cat.

Spreading Giardia

Beavers aren’t the only guilty party with this disease

You may see giardiasis referred to as “Beaver Fever,” since beavers are believed to be a major source ofgiardial contamination of streams and ponds. However, many species can contribute to contamination of water sources, including humans, livestock, and deer. Various groupings of giardia are referred to as “assemblages.” Think of these as “species” of this protozoal parasite. Cats are susceptible to Assemblage F and A1. Humans are susceptible to Assemblage A1.

Metronidazole and fenbendazole are most commonly used to treat clinical cases of giardiasis in cats. These are off-label uses of the drugs, but with careful dosing, they have been used in cats successfully and safely for years. Unfortunately, some giardial resistance to these drugs is developing, so repeat treatments may be required.

It is important to disinfect living areas thoroughly to get rid of giardial oocysts. It may also help to bathe your cat right before treatment to remove any cysts that may be on her hair. In addition, try to determine where she got the giardia to begin with and take action to avoid those areas. That might mean keeping your cat indoors, which is always a safe option.

If your shelter or cattery becomes infected with giardia, you must treat all the cats, bathe them, and then house them in a clean area while you thoroughly disinfect the primary living quarters. Consider quarantining and testing any cats or kittens you plan to add to group housing to ensure that they do not have giardia. Practice excellent hygiene while handling infected cats and during cleaning, since Assemblage A1 can infect people.

There is a giardia vaccine, but this is not a core vaccine, which means it is only recommended when you have a widespread, chronic problem that is not responding to cleaning and treating. Vaccination is best as a preventive measure, so the giardia vaccine may be recommended for high-risk cats or where giardia infestations are persistent. The vaccine does not seem to assist in treatment, however, it may reduce shedding of cysts, allowing you to gradually get ahead of the protozoa.

Cryptosporidiosis

Cryptosporidium felis is a protozoal parasite that has many similarities to coccidia. Normally, it is host-specific and prefers to set up camp in the small intestine. The diarrhea can lead to dramatic fluid loss, which is most dangerous in young kittens. Luckily, healthy adult cats can generally mount an immune attack and fend off this parasite.

Cats acquire these protozoa via fecal-contaminated food, water, or soil. The sporulated oocsyts can exist in the environment and are resistant to many disinfectants, including the chlorine used in municipal water-treatment plants. Diagnosis requires microscopic examination of a fresh stool sample or an ELISA test.

Treatment requires the use of tylosin or azithromycin. Post-treatment fecal rechecks are recommended.

Prevention

These tiny parasites often occur concurrently in stressed cats or cats with immune deficiencies. It is important to evaluate fecal samples carefully and to perform follow-up rechecks.

Careful disinfection, along with bathing all cats in the household or group, can help to reduce the incidence of these infections.

Keeping cats indoors so they have limited exposure to infected soil and water will also help. Provide your cats with good nutrition, parasite control, and regular veterinary care. A healthy adult cat can often fend off these infections via her own immune system.

Quarantine

Avoid spreading the protozoa

If possible, quarantine any new additions to your feline family for at least two weeks. During that time, run at least two fecal checks, and possibly ELISA testing, to look for any parasites. If you find any parasites, treat as indicated by your veterinarian and then recheck fecal evaluations. Bathe the new additions right before adding them to your household and again when they are cleared to leave quarantine.