Advances in veterinary medicine and an increase in animal blood banks have improved the diagnosis and treatment of hemophilia to the extent that some cats who once would have died from the life-threatening disorder can now live full lives.

The Comparative Coagulation Laboratory at Cornell University of Veterinary Medicine is at the forefront of developing techniques for early diagnosis of hemophilia. The laboratory acts as a specialized coagulation testing center for veterinarians throughout North America, offering sophisticated tests that might not be available in private practices.

The simple screening tests performed in private practices may provide clues that the patient has a bleeding disorder, says Marjory Brooks, DVM, ACVIM, Director of the Laboratory at Cornells Animal Health Diagnostic Center, explaining that the lab follows up with tests on coagulation (blood clotting) and platelets (cells that help blood clot) to pinpoint a specific diagnosis. The tests are critical for appropriate treatment.

Reduced Clotting. Hemophilia is a disorder in which the bloods ability to clot is reduced, causing a cat to bleed severely from even a slight injury. The incidence in people is well documented at one case per 10,000 male births.

We think the same incidence is likely in cats, although the numbers of cases that will be diagnosed is much lower, Dr. Brooks says. There is no drug or diet supplement that can supply the missing coagulation factor in pets with hemophilia. However, transfusion with feline blood products is effective. Products include whole blood, packed red blood cells and frozen plasma.

Potentially Fatal. The number of transfusions required throughout an affecteds cats lifetime depends largely on the conditions severity. Several types of coagulation factor deficiencies affect animals, such as dogs, mice and sheep, as well as cats and humans. Many types result in severe, prolonged bleeding due to the lack of coagulation. Cases become potentially fatal if a cat suffers injury or undergoes surgery. In more severe cases, internal bleeding can occur in the abdomen, chest, central nervous system or muscles, and an owner might not detect it until the cats life is in jeopardy.

Hemophilia A (known as factor VIII deficiency) is the most common inherited bleeding disorder in cats. Veterinarians often find that the severity and frequency of bleeding are related to the degree coagulation factor VIII is decreased (or in some cases, completely absent) in the blood.

Cornell

Hemophilia B (known as factor IX deficiency) is diagnosed less often in cats. Signs of both types are similar, and when related to blood-loss anemia and internal bleeding, additionally

can include:

– Weakness

– Lethargy

– Excessive bruising

– Frequently bleeding gums

– Swollen, tender joints

– Shortness of breath and irregular heart beat

– Lameness when bleeding occurs into joints or muscles

– Hematoma, a swelling filled with blood

Cases of internal bleeding also can result in blood in the stool or vomit. Anemic cats (due to hemophilia or other disorders) may also develop pica – compulsively eating stones, dirt and feces.

The ratio of cases of hemophilia A to B is approximately five to one, Dr. Brooks says. Both forms are sex-linked (or X-linked) recessive. This means that males demonstrate the bleeding tendency, and female carriers show no symptoms of the condition. However, a female carrier can transmit the trait for hemophilia to her offspring. On average, a carrier female will transmit the trait to half her sons (who are then affected with hemophilia) and to half of her daughters (who are then also carriers).

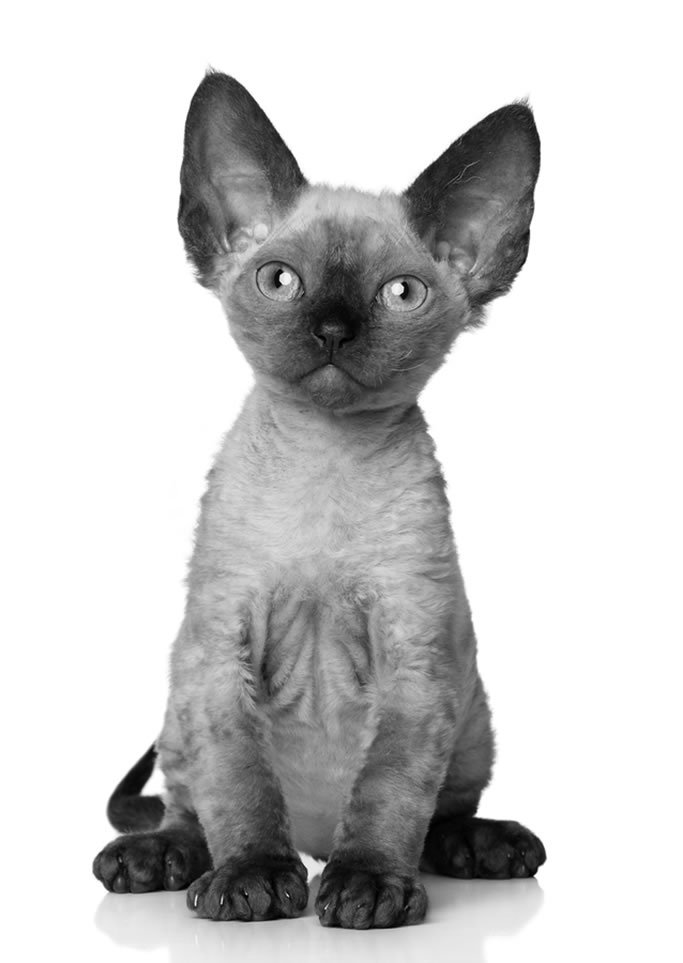

Hemophilia can affect domestic cats of any breed, with specific case reports describing hemophilia in Maine Coon and British and Devon Rexes. Hemophilia often results from spontaneous mutation in previously unaffected breeds or lines, Dr. Brooks says. Unlike many hereditary traits, hemophilia is often diagnosed in mixed-breed animals and is not exclusively found in a single breed or inbred family.

However, once a mutation develops, it can be propagated when asymptomatic carrier females or mildly affected males are bred.

Given the heritable nature of hemophilia, diagnosing affected cats, as well as female carriers, is vital to maintaining responsible breeding practices.

Various Degrees. The severity of hemophilia varies widely. Some cats might die within the first few weeks of their lives, while others live full lives with only intermittent signs of bleeding. The disease is often diagnosed when a young male develops severe, abnormal bleeding after neutering, Dr. Brooks says. In the most severe forms of hemophilia, kittens have spontaneous hemorrhage into muscles and joints (causing lameness and swelling) and prolonged bleeding when teething and from minor wounds.

Veterinarians diagnose hemophilia with an evaluation of coagulation in specially prepared blood samples. In cases of hemophilia A, the tests measure the coagulation factor VIII. Hemophilic cats have a marked reduction in factor VIII activity compared to normal cats.

Because hemophilia has a known inheritance pattern, pedigree information can streamline diagnoses and identify carrier females.

Bigstock

The blood products used to treat patients with hemophilia include fresh frozen plasma that replaces both factor VIII and factor IX components of the blood.

If a hemophilic cats blood loss is severe, he will be hospitalized and receive transfusions. Repeated transfusions might be necessary to control or prevent further hemorrhaging. Including hospitalization, blood typing tests and the transfusions themselves, the costs can range from several hundred to several thousand dollars, depending on the conditions severity.

Transfusion can cause immune reactions in a cat when antibodies in the recipient destroy the foreign blood cells or proteins from the donor. However, blood typing and cross-matching tests are now widely performed in veterinary medicine. The need for transfusion varies depending on the patients clinical bleeding tendency, Dr. Brooks says. Severe cases may require frequent transfusion and may experience frequent, spontaneous bleeds that impact quality of life. Patients with mild to moderate hemophilia may have a natural life span with few or no transfusions.

As veterinary testing and management of hemophilia in cats continue to improve, so too do the ultimate outcomes for them.