Cats are special in many ways, and that often applies to diseases they develop — but not always in a good way. Consider heartworm disease. We tend to think of it as a problem in dogs, not cats, but that’s a misconception — one that can be deadly for cats.

They are indeed less commonly infected by heartworms than dogs, and approximately 80 percent of infected cats clear the infection without signs of disease, but studies have shown the incidence of infection to be greater than previously thought. One study found that between 2 and 5 percent of shelter cats were harboring heartworms. Other statistics show that the prevalence of heartworm disease in cats likely approaches 5 percent, and that it can even occur in cats living indoors.

Even worse: “While the incidence of heartworm disease is low in cats compared to dogs, their clinical signs can be more severe,” says Leni Kaplan, MS, DVM, a lecturer in the Community Practice Service at Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine.

Sudden Signs

Clinical signs, which usually don’t occur until infection is well established, can appear suddenly and dramatically. “They can include salivation, vomiting and diarrhea, collapse and neurologic signs such as altered mentation, blindness and seizures,” Dr. Kaplan says.

The most common signs of heartworm disease in cats, however, include coughing, gagging, difficulty breathing and wheezing. These signs are secondary to a syndrome known as heartworm associated respiratory disease, or HARD. In some cases, though, the symptoms can be vague and may include inappetance, lethargy, exercise intolerance, and/or weight loss.

While cats may have as few as one to three adult heartworms, even immature heartworms can damage the feline heart and lungs. Blood clots can develop in the blood vessels in the lungs, and the walls of these vessels can become inflamed. Sometimes the only sign is sudden death.

Heartworm disease often goes undiagnosed in cats, but that doesn’t mean the worms — which migrate to the heart, lungs and associated blood vessels — aren’t present. Cats are not typical hosts for heartworms, known scientifically as Dirofilaria immitis, but they can acquire the spaghetti-like worm through the bite of a mosquito that has fed on the blood of an infected dog, fox or coyote, to name the most likely possibilities.

The bite injects infective larvae into the body, where they enter the bloodstream and begin their life cycle and migration toward the heart and lungs. If they mature, the heartworms can live two to three years in a cat’s body, sometimes growing to nearly a foot in length. They don’t always limit themselves to the heart and lungs, and can also migrate to the brain, eye and spinal cord.

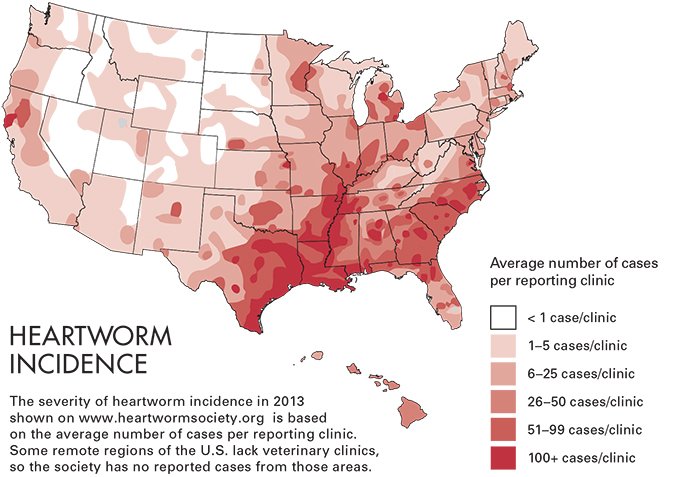

American Heartworm Society

Adaptive Mosquitoes

Heartworm disease is usually associated with the Deep South, with its hot, humid climate that is so attractive to mosquitoes. The truth is that mosquitoes can adapt to many climates. The greatest number of cases occurs in the Mississippi River Valley, the Atlantic and Gulf coasts, and in Texas, but pets have been diagnosed with heartworm disease in every state, including Alaska and Hawaii. If dogs or wildlife in your locale are infected with heartworms, your cat is at risk, too. Don’t think your cat is safe if he spends all his time indoors. How many times have you swatted a buzzing mosquito inside your home?

Blood tests can be used to determine the presence of the worms, but they are not completely reliable alone. Veterinarians usually rely on a combination of signs and other tests. For the most accurate results, your cat’s veterinarian may recommend using both an antigen test to detect adult worms and an antibody test to detect a cat’s immune response to heartworms, although the latter is likely more useful, given the low numbers of heartworms usually present in infected cats. The presence of heartworms can, in some cases, be verified through the use of echocardiography (cardiac ultrasound).

Prevention is the best medicine when it comes to feline heartworm disease. Talk to your cat’s veterinarian about the recommended product for your area. Your cat should be tested to make sure he’s free of heartworms before he can begin taking the preventive.

No treatment is available for feline heartworm disease. While dogs can undergo a series of intramuscular injections of a drug to kill the worms, the medication is generally considered to be toxic to cats. In many cases, feline heartworm infections disappear on their own because cats are not the preferred host and/or because they develop an immune response that kills the worms.

However, cats can still develop HARD before the worms die off, and the immune response — resulting in inflammation — can cause many of the signs commonly seen in infected cats.

Although specific therapy geared toward killing the adult worms is generally not administered in cats, the signs of infection can often be managed. Infected cats may benefit from supportive treatment such as intravenous fluids, oxygen therapy, corticosteroids and in some cases cardiovascular drugs.

While surgical extraction of worms is theoretically possible, this option is rarely pursued unless high worm burdens cause life-threatening clot formation and obstruction of blood flow in the blood vessels of affected cats.

Other clinical signs such as vomiting can be managed with medication. In the best-case scenario, an affected cat’s condition will stabilize over time and the worms will die off naturally.