Feline dermatophytosis (FD) is among the most frequently occurring skin disorders affecting the worldwide cat population. Although the condition is commonly called ringworm (even by veterinarians), it is a fungal infection having nothing at all to do with worms. And the only thing it has to do with rings is the circular area of itchy rash that may – but wont necessarily – appear on the skin of an infected animal or human. The disorder was given its misleading name centuries ago by people who believed it was caused by an insidious little creature that wormed its way into a persons circulatory system and curled up neatly beneath the victims skin.

The Chief Culprits

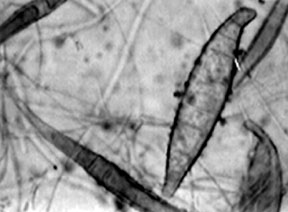

The fungi responsible for FD are called dermatophytes, microscopic organisms that originate in soil but can flourish as parasites beyond their home environment. The vast majority of FD infections are caused by the dermatophyte Microsporum canis (M. canis), which invades the skin, claws, and, most problematically, the outer layers of a cats hair coat. Once entrenched, the fungi thrive by digesting keratin, a protein substance that is the main structural component of hair and nails. As they feast on keratin – usually in the tissue of dead and shed skin and hair – the microscopically tiny fungi reproduce quickly and horrifically, creating millions of single-cell reproductive bodies (spores) that are capable of developing into new microorganisms.

When the dermatophytes come into contact with healthy feline tissue, several different phenomena may occur: They may be brushed off by a meticulously self-grooming cat; they may lose out in competition with more robust microorganisms and eventually disappear; or they may establish residence on the skin without causing any adverse reactions. In the worst case, however, they may settle in droves on the animals skin and cause dermatitis – an inflammatory disease that can manifest itself in a variety of unpleasant ways.

The Ideal Environment

The disease appears to be more prevalent in tropical and subtropical areas with warm, muggy climates. According to Karen Moriello, DVM, research suggests that FD is associated with about two to three percent of all reported feline medical complaints worldwide. Depending on the demographics, youll see either very little or a lot in a given area, says Dr. Moriello, who is a clinical associate professor of dermatology in the School of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

288

In hot, damp areas that favor the organisms growth, anywhere from 30 percent to 80 percent of sampled stray cats have tested positive for dermatophytosis. In cooler, drier areas, it can be as low as four percent to five percent. The prevalence varies tremendously, says Dr. Moriello. Seasonal variations (warm weather versus cool) have also been cited as influences on the occurrence of FD.

Although FD is generally a mild disease that may simply vanish over time, says Dr. Moriello, the real problem is that it is highly contagious among cats and is a zoonotic disease – it can be passed to humans. These two factors make FD a public health concern that can have significant economic impact. That is why we advocate treatment of it, rather than just letting it resolve spontaneously.

Cats At Greatest Risk

According to Dr. Moriello, cats that are exposed to M. canis and who are, for one reason or another, unsuccessful self-groomers are far more likely than other felines to contract FD. Thus, kittens that have been taken from their mothers before being taught good grooming habits are at greater risk. The same goes for long-haired cats that are likely to have trouble with thoroughly grooming their dense coats, and arthritic cats, whose grooming capability may be physically restricted. Flea-bitten cats, too, are especially vulnerable, since the fungus can readily establish itself in a warm, wet bite wound.

In addition, outdoor cats that are allowed to roam freely in areas that may be contaminated by fungus are at greater risk than indoor cats. And animals living in multiple-cat homes, catteries, shelters and pet shops can easily spread any fungus that is brought into the environment. The more animals you have, Dr. Moriello points out, the more difficult it is to protect against dermatophytosis. So if the environment becomes contaminated and you have lots of cats, youre in a very tough situation.

Signs to Look For

The most common clinical signs of FD include the following: circular areas of hair loss, broken and stubbly hair, scaling or crusty skin, alterations in hair or skin color, inflamed areas of skin, excessive grooming and scratching, dandruff, infected claws or nailbeds – and even lameness resulting from those infections. If any or all of these signs are observed, an owner should consult a veterinarian without delay for appropriate testing and, if the cat turns out to be culture-positive, for treatment.

Some cats, Dr. Moriello adds, may mechanically carry harmful fungi but show no signs of infestation at all. Consequently, she recommends that all cats that are newly introduced into a household be screened by a veterinarian for possible M. canis contamination – especially if the animals previously resided in a multiple-cat environment.

288

Because many other dermatologic conditions – like flea allergy – may mimic M. canis, the initial step is to rule out dermatophytosis, says Dr. Moriello. To achieve this, the veterinarian may start by examining the cats coat with a Woods lamp – an ultraviolet light under which a fungus-coated hair will often radiate (flouresce) a yellowish-green color. Next, any hairs that fluoresce are examined microscopically for specific spores and other fungal characteristics. If those characteristics are revealed, indications are that the flourescence was indeed caused by M. canis and not by some metabolic byproduct that would also glow under the light of the Woods lamp.

The third and most reliable diagnostic step is a fungal culture, which will cost the cat owner $20 or less. This is minimal, says Dr. Moriello, compared to the cost of treatment if the fungus remains undetected and the animal gets really ill. In this procedure, suspect cat hairs that flouresce or that have been collected with a sterile toothbrush are placed in a culture medium, incubated for several weeks, and then examined for indisputable signs of M. canis growth. If the culture is positive, the cat is known to be hosting the ringworm fungus – and treatment must be initiated immediately.

Solving the Problem

Treatment of FD may be done either at a veterinary clinic or, more economically, at home. For owners who opt for the latter, Dr. Moriello describes three steps that are to be taken:

Clipping of the hair coat: Use a blunt-tipped childs scissors or an electric clipper to trim the hair around all lesions as closely as you can – to a length of about two centimeters.

Topical antifungal therapy: Dip the cat in a solution of warm water and topical antifungal agents recommended by your veterinarian. For a cat that resists this method of whole-body therapy, wrap the animal in a towel, gently submerge it, and let the solutions soak through the towel. This should be done twice a week.

Systemic antifungal therapy: Start giving your cat oral antifungal medications – such as griseofulvin, itraconazaole or terbinafine – on a schedule determined by your veterinarian.

After a month or so, says Dr. Moriello, the owner should collect a sampling of hairs with a sterile toothbrush, place the brush in a double zip-lock bag, and take it to the clinic for another culture. This should be done every two to four weeks until the cat is rid of the fungus. The cure has been achieved, she says, when three cultures in a row prove negative.

The owner should not be discouraged, says Dr. Moriello. Treatment normally will take as long as three months or so, although some cats may be cured of the fungus more quickly.