vadimphoto1@gmail.com | Deposit Photos

A diagnosis of hip dysplasia might take you by surprise. Usually, a cat comes into the veterinarian because the owner notices that the cat is lame or sore, or less active than normal. Some cats with hip dysplasia will be consistently off in their gait, while other cats only show stiffness after a wild chase through the house.

And, cats being cats, some never show obvious lameness because they limit their activity to nonpainful moves themselves. In these cats, however, you’ll probably see the change in their activity level, such as a cat that would routinely leap up to check out things on the counter staying on the floor.

Hip dysplasia isn’t something we normally think of in cats. Dogs, yes. However, cats can have hip abnormalities and hip arthritis as well. Just as in dogs, hip problems tend to be seen in the bigger-boned, heavier breeds of cats, such as Maine Coon cats. Still, even small, lithe cats like the Devon Rex can develop hip dysplasia, as can domestic shorthairs.

What Is Dysplasia?

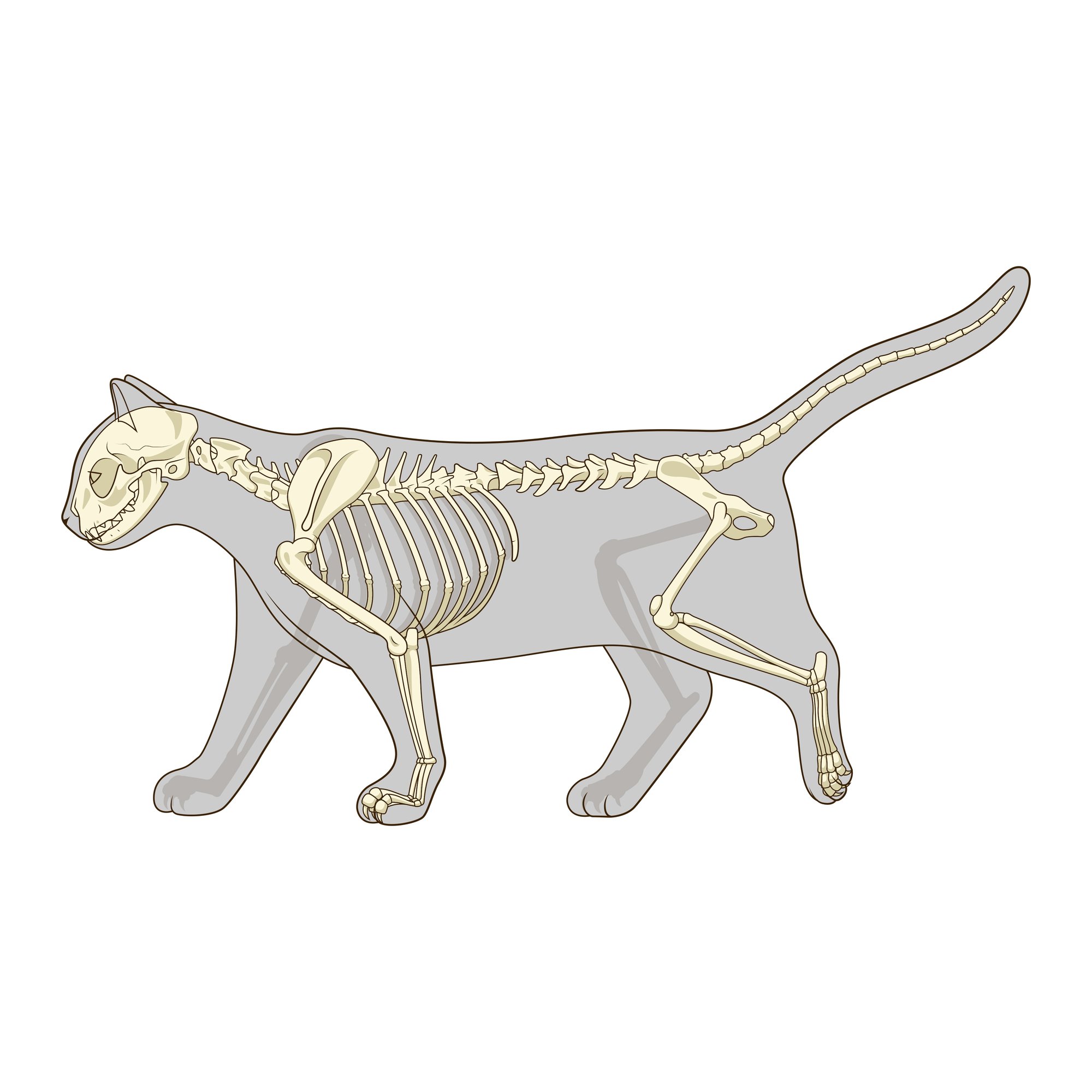

Hip dysplasia appears to be a multifactorial condition, involving primary and modifier genes, as well as being influenced by various environmental factors. Dysplasia means abnormal growth or development. Hip refers to the hip joint, which is a “ball and socket” joint that connects the femur to the pelvis. The head of the femur is the “ball” that fits into the “socket” of the acetabulum of the pelvis. Ideally, your cat has a clean, round femoral head and nice deep acetabulum to stabilize the joint.

This connection is not bone-on-bone, of course. There is articular cartilage and joint fluid between the bones to reduce friction and keep the joint working smoothly. The muscles also help to stabilize the joint and can minimize malfunction and malformation effects.

In hip dysplasia, the acetabulum may be shallow, so it does not hold the femoral head firmly in place. This can even be a subluxation (misalignment) due to the femoral head sliding out of the socket area of the acetabulum. The femoral head itself may not be smooth and round or there may be joint laxity that leads to small, repeated traumas within the joint every time your cat moves. Generally, both hips will show some degree of dysplasia in affected cats, although it may be worse on one side.

The Diagnosis

It can be difficult for a veterinarian to diagnose lameness in a cat just by physical examination. A thorough history can help. For example, if you got your cat as a stray, it is possible he was hit by a car sometime in his past.

Ideally, your veterinarian would like to see your cat move, preferably in a straight line. Cats, of course, usually have their own ideas about that. At the veterinary clinic, they’ll probably simply hunker down and refuse to move. So, the veterinarian will use manipulation of the joints to find areas of pain. Even then, though, some cats are quite stoic, especially in unfamiliar surroundings.

Both PennHIP, a radiographic screening method for hip evaluation, and the OFA (Orthopedic Foundation for Animals) provide protocols and testing for hip dysplasia in cats, based on existing dog protocols.

Radiographs (i.e, x-rays) will be needed to evaluate the bones of the hip joint and usually require sedation both to ensure the cat’s cooperation and to minimize pain from an arthritic joint.

The standard view is with the cat lying on her back and her hind legs stretched out straight. This view is like the evaluation radiograph required for OFA certification of the degree of dysplasia in the hip. (The OFA classifies hips into seven different categories: Excellent, Good, Fair, Borderline, Mild, Moderate, or Severe.) Additional views are done for PennHIP certification, which looks at measurements of joint laxity as well as hip-joint conformation.

When radiographs are sent to OFA or PennHIP, veterinary radiologists take measurements and compare the radiographs to those of normal cats. Ideally a cat’s radiographs would be compared to a cat of the same breed as well. Currently, only Maine Coon cats have enough cats in the registries to make this comparison reasonable.

Bony or osteo arthritis in the hip may be a result of hip dysplasia or it can be from trauma to the joint area. Bad falls, being hit by a car, and even the extra effort from being overweight can contribute to arthritis in the hip. With some cases, it may be difficult for your veterinarian to distinguish between genetic hip malformations and trauma if the joint is badly affected when viewed on x-rays. Still, one study of randomized cats showed a 32 percent incidence of hip arthritis compatible with hip dysplasia.

Treatment and Prognosis

What do you do if your cat is diagnosed with hip dysplasia? Luckily, with their smaller body size and good muscle mass, many cats with hip dysplasia never show any signs of problems. What you need to do depends upon whether your cat shows clinical lameness or not. Some cats will have hip dysplasia on x-rays but not show any signs. For these cats, you may simply need to watch carefully and consider a joint supplement to minimize the development of any arthritis.

Watch your cat’s weight. Being overweight means more stress on joints. Encourage your cat to be active, but try to limit big leaps. Cat agility is becoming a popular sport (catagility.com), but it’s not a good idea with hip dysplasia!

If your cat shows frequent or constant bouts of lameness, your options are somewhat limited. Pain and anti-inflammatory medications can help.

If your cat does not respond well to one combination of medications, discuss other options with your veterinarian. Just as some pain medications work well for one person while someone else swears by a different drug, cats may have individual differences in response to the medications, too.

Those drugs may be enough for some cats. You can also do environmental modifications, such as moving the litter box upstairs, so your cat doesn’t have to venture into the basement. Surgery is also an option in some cases of hip dysplasia (see sidebar).

Preventing hip problems means keeping your cat fit and trim. Avoid extreme exercise—including big leaps—especially when your cat is young and growing. Do encourage moderate exercise and keep your cat active.

If a big-boned breed of cat is your heart’s desire, ask about hip evaluations on the sire and dam of the litter you’re considering. Normal parents aren’t a guarantee of clear hips, but it puts the odds in your favor. Remember that many cats handle hip dysplasia and hip arthritis fine, with a little management help from their owners.

AlexanderPokusay | Deposit Photos

Surgery Options for Cats

Small bones make surgery more difficult

Surgery may be in store for cats with severe and painful cases of hip dysplasia. Total hip replacements can be done but are very uncommon. Cat bones are small and somewhat fragile, so they don’t always hold implants well.

“You can just remove the femoral head—the ball part of the hip’s ball-and-socket joint—and not replace it,” says Ursula Krotscheck, DVM, DACVS, Cornell College of Veterinary Medicine Associate Professor, and Section Chief of the Small Animal Surgery Section. “The muscles that normally hold those components of the hip will essentially continue to do their job, but without the painful bone-on-bone contact.

“Although the cat may have a mechanical lameness and the affected limb may be a little shorter after the operation, the leg usually will have an almost normal range of motion and excellent function. The animal usually will be able to sit up, run, jump, and engage in normal cat behavior.”

Cats who undergo surgery will require rest and then rehabilitation post-operatively. Many cats go back to full normal activity.