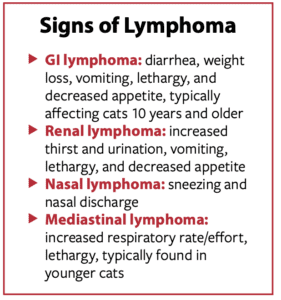

Lymphoma is the most common cancer in cats. While it can occur anywhere in the body, the most common form in cats is gastrointestinal (GI), followed by renal (kidneys), nasal, and mediastinal (space in the chest cavity that contains the heart, trachea, and other important structures).

“GI lymphoma comprises over 50% of feline lymphoma cases,” says Dr. Skylar Sylvester, assistant clinical professor of medical oncology at Cornell University’s College of Veterinary Medicine.

Lymphoma affects lymphocytes, which are circulating white blood cells that play a key role in the immune system. Because it affects cells that travel throughout the body via the lymphatic system, lymphoma can spread (metastasize) quickly from one site to another in the body.

Causes

While the cause of lymphoma in cats is unknown, certain factors are strongly suspected as playing a role in its development. Cats infected with feline leukemia virus (FeLV) and/or feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV), for example, are at greater risk of lymphoma.

While the cause of lymphoma in cats is unknown, certain factors are strongly suspected as playing a role in its development. Cats infected with feline leukemia virus (FeLV) and/or feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV), for example, are at greater risk of lymphoma.

There are presumed genetic predispositions (Siamese cats appear to be at greater risk for developing lymphoma) and environmental influences (such as exposure to second- hand smoke) that may play a role, as they may in human lymphoma.

Chronic inflammation at injection sites may result in the rare development of cutaneous (skin) lymphoma.

Diagnostics

A biopsy is the only definitive way to diagnose lymphoma, although some diagnostic findings can be suggestive of lymphoma in the absence of biopsy results. The results of a fine needle aspirate, for example, can be highly suggestive of lymphoma in some cases.

Ultrasound can be useful in diagnosing feline lymphoma, especially with the GI form, although distinguishing GI lymphoma from inflammatory bowel disease based solely upon this diagnostic test in cats can be problematic.

Another challenge is that without the benefit of a biopsy, there is no way to know if a cat with GI lymphoma has low-grade or high-grade disease. The grade of lymphoma affects treatment choice and can significantly affect outcomes in cases of feline GI lymphoma.

Treatment

“Chemotherapy is the most effective treatment for lymphoma,” says Dr. Sylvester. “The exact chemotherapeutic drugs and schedule will depend upon the extent of disease (cancer stage), how aggressively the cancer is behaving, how sick your cat is at the start of treatment, any abnormalities in organ function (particularly kidneys and liver), and the goals of treatment.”

“There are two types of lymphoma seen in the gastrointestinal tract of cats: small-cell low-grade lymphoma and large-cell high-grade lymphoma,” says Dr. Sylvester. “They are treated with different types of chemotherapy and have different prognoses. Cytology or biopsy is needed to differentiate between the two types. The treatment for small-cell gastrointestinal lymphoma is oral chemotherapy given at home, and cats can live one to two years or more with this treatment. Large-cell lymphoma is a much more aggressive cancer, cats typically present with severe illness from their cancer and are treated with front-line multi-agent injectable and oral chemotherapy (the CHOP protocol), with survival often less than three to six months with treatment.”

Despite this, Dr. Sylvester says not to lose hope. “There are some cats with large-cell lymphoma that achieve a complete remission with chemotherapy and can survive longer.”

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy can be a scary thought for pet owners, as our human counterparts undergoing chemotherapy often feel awful and suffer unpleasant side effects. This is usually not the case in cats.

“In general, cats tolerate chemotherapy well, with minimal side effects,” says Dr. Sylvester. “The most common side effects are decreased appetite and weight loss, but other signs such as vomiting and diarrhea, lethargy, and low white and red blood cell counts can occur. Cats do not usually lose their fur, but they may lose their whiskers during chemotherapy.”

Nobody, especially your veterinary oncologist, wants your cat to feel sick while undergoing treatment for lymphoma. “The goal of cancer treatment is to maintain or improve a cat’s quality of life, so if side effects from chemotherapy occur, we can consider either lowering the dose of the drug or substituting a different drug,” says Dr. Sylvester. “Serious side effects resulting in hospitalization occur in less than 10% of cats treated.”

Perhaps a bigger concern than potential side effects for cat owners contemplating chemotherapy for their cat is whether they can handle having to administer daily oral medications. This can be quite challenging. Additionally, careful follow-up and monitoring is important, which means getting your cat into a carrier and to the oncologist’s office on a regular basis.

If your cat is diagnosed with lymphoma and chemotherapy is not for you, palliative treatment and supportive care can buy you some extra time with your beloved cat. The duration of this time may not be long, but an affected cat’s quality of life can be very good for as long as it lasts.