Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is one of the most common cancers seen in cats. You may be familiar with the classic form of this disease, which is a skin cancer that affects white cats on their ears and faces. We will discuss the skin cancer first, but you should know that there is a deadlier type that is much more difficult for owners to notice and much harder to treat: oral SCC.

Epithelial Cells

Lets start with skin cancer. The skin is made up of layers of epithelial cells. Epithelial cells cover other surfaces in the body, including the oral cavity. SCC is a cancer of epithelial cells.

In cats and humans, ultraviolet light exposure from the sun has been proven to contribute to the development of cutaneous SCC. This is likely why white cats with lightly pigmented skin, like fair-skinned people, are more prone to cutaneous SCC. It typically strikes the ears, particularly the outer edges, but can occur on the eyelids and nose.

“People are advised to minimize their exposure to direct sunlight during peak daytime hours in order to decrease skin cancer risk. This is important for cats as well,” says Kelly R. Hume, DVM, DACVIM, associate professor of oncology at the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine.

As with any cancer, prevention and early detection are key. To help prevent the cutaneous form of SCC, keep your light skinned, white cat indoors. If she goes out, apply sunscreen to her ears and any sparsely haired areas. Make sure the sunscreen you choose does not contain zinc, as this can be toxic to cats if ingested while grooming, and always check with your veterinarian before applying any sunscreen products to your cat.

Other potential causes of SCC include infection with papilloma virus (papilloma virus DNA has been identified in feline cutaneous SCC tissue), genetic predisposition, and/or gene mutations.

Todorean Gabriel | iStock photo

Crusty Lesion

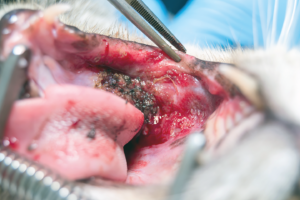

Cutaneous SCC typically looks like a crusty spot that doesn’t go away. It usually doesn’t seem itchy and usually doesn’t appear to be painful. The lesion may get bigger with time, become plaque-like, redder, and the surface could ulcerate. If secondary bacterial infection sets in, then it may become itchy and/or painful.

If you see something like this on your white-faced cat, go to your veterinarian as soon as possible. Your veterinarian may do some preliminary testing to rule out other potential causes of the skin lesion (e.g., mange, ringworm). If these tests are negative, a biopsy is usually recommended. If the lesion is in an area that is amenable to removing it in its entirety, with wide margins, this should be done, and the tissue should be submitted for biopsy.

If you are lucky, the biopsy will come back pre-cancerous, and your quick action will have paid off big time, essentially preventing cancer.

If the biopsy comes back SCC, and the surgical margins are clean (clear of cancer cells), this will often result in good long-term control, as cutaneous SCC is slow to metastasize (spread to other organs in the body).

If the margins are dirty (i.e. they contain cancerous cells), or if the lesion was in a place where complete resection with wide margins was not possible (e.g., eyelids), the prognosis is usually less favorable. Extensive and/or invasive lesions are difficult to treat, thus the poorer prognosis. Complete surgical removal will always be the best chance for cure.

Conventional chemotherapy usually doesn’t work. Electrochemotherapy (electric fields applied to cancer cells to make them more susceptible to chemo drugs) is showing promise. Radiation therapy, which requires multiple treatments under general anesthesia, works for some lesions.

Options for small, superficial lesions include cryotherapy (freezing the tissue to destroy it), topical treatment with an immune modulating cream (Imiquimod 5%), and plesiotherapy.

Plesiotherapy is high-dose radiation using a Strontium-90 probe, and a single treatment can be curative. Unfortunately, this treatment requires special equipment and is not available at all oncology centers. According to Dr. Hume, plesiotherapy for cutaneous SCC is offered at the Cornell University Hospital for Animals, but it only works for small, superficial lesions.

Deadly Oral SCC

In the mouth, SCC tends to be much more aggressive and invasive than on the skin. Making matters worse, it’s harder to catch early, as most owners are unaware of the lesion until it starts causing obvious problems like drooling, bad breath, decreased appetite, reluctance to eat, oral pain, and/or weight loss. Its location usually makes surgical removal difficult, and radiation therapy is fraught with complications due to potentially debilitating side effects.

The most common location of oral SCC is under the tongue, right at its base. It also occurs on the gums along the upper and lower jaw and can occur in the tonsillar area as well.

While surgery is still the treatment of choice, it is difficult to completely remove a cancer, with wide margins, in the mouth. This usually entails aggressive, disfiguring surgery, after which many cats have a difficult time functioning. Some will require hand feeding for life, or even surgical placement of a stomach feeding tube.

If an oral mass has been identified in your cat, work with a veterinary oncologist. This specialist will discuss all available options for your cat’s individual situation, the pros and cons of each, potential complications, and expected outcome.

“It is very hard to successfully treat oral squamous cell carcinoma if there isn’t a surgical option,” says Dr. Hume, “So, finding these tumors when they are small is really important. Routine dental exams with your veterinarian and regular oral care and evaluation at home can help with early detection.”

What You Can Do

- Keep light-skinned cats out of sunlight as much as possible.

- Consider a cat-safe sunscreen if the cat is an indoor-outdoor cat.

- Have crusty lesions that don’t show improvement within a week examined by a veterinarian.

- Watch for early signs of oral SCC, such as drooling or bad breath.

- Keep up twice-a-year wellness exams for cats 7 years old and older.

When Hope Dwindles

When there is little hope for cure, or if the potential complications and side effects of treatment are too daunting, palliative care is commonly pursued. This is geared toward improving and maintaining comfort and quality of life for as long as possible. It is frequently elected for chronic diseases for which cure is unlikely, such as oral SCC in cats.

The mainstay of palliative care is pain management. Buprenorphine is an effective opioid pain reliever in cats and is easy for owners to administer by mouth at home. As such, it is frequently the first medication prescribed. Tramadol is another opioid that is effective for pain in cats. Gabapentin is a neuropathic pain reliever that can help with oral pain, especially when added to an opioid regime.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are good for relieving pain and reducing inflammation. They must be used cautiously in cats, and with veterinary supervision, as they can be harmful to the kidneys. Some NSAIDs are toxic to cats. Meloxicam (Metacam) and robenacoxib (Onsior) are NSAIDs approved for use in cats.

A potential secondary benefit to NSAIDs is that some SCC cases have an overabundance of the receptors (COX 1 and COX 2) that NSAIDs bind to in cells. This means that it is possible NSAIDs may slow the progression of SCC. As such, your veterinarian may prescribe meloxicam or robenacoxib for your cat. Piroxicam is a powerful NSAID that has been shown to slow the growth of other cancers. Because of its potential to cause harm in cats, however, its use should be limited to the discretion of a veterinary oncologist.

Bisphosphanates (drugs that slow bone loss, such as are used for human osteoporosis) have been used as part of palliative care for cats with SCC. These drugs may help keep cats with underlying bone involvement feel better longer, as they slow bone loss associated with cancerous infiltration of bone.

On the home-management front, soft or canned food will be easier for a cat to pick up, chew, and swallow than dry food. Appetite stimulants like mirtazapine are often necessary and helpful.

Treating any secondary bacterial infections in the mouth is important for your cat’s comfort as well. Increasingly bad odor from the mouth and purulent-looking drool are common indicators of infection.

For oral SCC, while there’s not much you can do to prevent it, having any cat over 7 years of age examined by a veterinarian twice a year may help catch it early. Thorough oral examination, including looking underneath the tongue, can be challenging. If your veterinarian has a high index of suspicion based on preliminary oral examination, sedation or general anesthesia may be recommended so that a full evaluation can be performed.

t:rukawajung | iStock photo