Congestive heart failure, characterized by the accumulation of fluid in the lungs and other body tissues secondary to heart disease, might appear to strike suddenly. In many cases, however, it results from a progressive underlying disease that, if detected early, can be managed to improve and extend a cat’s life.

“Very often, we can help pets,” says cardiologist Bruce G. Kornreich, DVM, Ph.D., Associate Director for Education and Outreach at the Feline Health Center at the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. “There are medications that can decrease congestion in lungs, may decrease the likelihood of an animal developing blood clots and can improve oxygenation of the blood.”

bigstock

288

Offering Hope. Studies in several areas, including one on a promising diagnostic test, offer hope for cats with heart disease, as early diagnosis of underlying heart conditions is an important component of their management.

Veterinary researchers are evaluating whether and how the concentration of a molecule called brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) in the blood can be used to screen for feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, which can lead to heart failure. BNP is a compound released in the body when parts of the heart are dilated or stretched, as they may be in feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Studies at a number of U.S. and international institutions suggest that BNP can be used as an initial screening tool for feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy although there is some controversy regarding the appropriate application of this test in terms of grading disease severity and monitoring disease progression over time.

Another advantage of this test as a screening tool is the fact that it is relatively inexpensive. It is important to point out, however, that BNP concentrations are best used in conjunction with other diagnostic tests, including echocardiography and X-ray, in the diagnosis and management of cats with heart disease.

Owners should be aware of CHF’s early warning signs and call their cat’s veterinarian if they see them. The most common signs are difficulty breathing, lethargy and loss of appetite.

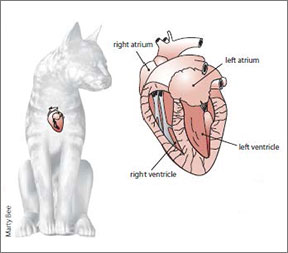

The Most Common. Feline hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is by far the most common heart disease in cats. The condition is characterized by thickening of the muscle of the left ventricle. The thickening interferes with the heart’s ability to pump blood properly. (Please see sidebar.) Two less common types of cardiomyopathy that can also lead to congestive heart failure are restrictive cardiomyopathy, caused by the excessive buildup of fibrous tissue in the ventricles, and dilated cardiomyopathy, which is characterized by a dilated and thin-walled, poorly contracting left ventricle.

Most conditions leading to CHF are considered “acquired” diseases, in that they develop during the course of a cat’s life. Congenital defects in the heart — ones present at birth — can also result in CHF. Because hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is the leading cause of CHF in cats, this discussion will focus on the diagnosis and treatment of this disease.

288

Although HCM can develop in cats of any gender, age or breed, certain cats are at greater risk. The disease most frequently affects males and, although it has been diagnosed in cats as young as 4 months of age, it is most commonly diagnosed in middle-aged cats. Certain breeds, including Maine Coons, Ragdolls and American Shorthairs, are predisposed to HCM, suggesting a genetic mechanism. Studies have thus far identified a number of mutations in cardiac proteins in feline HCM, although the definitive mechanism of this disease is still not known.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is sometimes not diagnosed until cats have gone into congestive heart failure and display the aforementioned difficulty breathing and lethargy, Dr. Kornreich says. In many cases, however, HCM is diagnosed after the identification of physical examination abnormalities during a routine checkup, before outward signs appear. In these cases, veterinarians might hear a murmur or irregular heart sounds and order further tests.

“We definitely see a spectrum of cases,” Dr. Kornreich says. “The disease might progress to heart failure, and the owner thinks, ‘Oh my goodness, this just happened.’ But in most cases, the disease has been progressing for a while.”

Reduced Blood Flow. In cases of HCM, the thickening of the heart wall reduces blood flow and oxygenation of tissues and organs throughout the body. Fluid often accumulates in the lungs, which causes breathing difficulty.

288

HCM can also result in the formation of blood clots within the heart. These clots can travel to other parts of the body, such as the arteries that lead to the rear legs.

As a result, Dr. Kornreich says a cat’s hind limbs might appear to be paralyzed and the cat may vocalize and appear very uncomfortable. “This is a very devastating thing to see,” he says. “In cases where a blood clot has formed, the prognosis becomes much less favorable.”

If a cat doesn’t display overt symptoms of heart disease, but a veterinarian detects an abnormality during a checkup, additional tests will often be recommended.

X-rays may be taken to rule out CHF, and sometimes an electrocardiogram or a blood test to identify heart muscle damage will be done. However, the gold standard for identifying HCM is echocardiography, which is an advanced method of imaging the heart that uses high frequency sound waves. The test can be expensive, says Dr. Kornreich, who estimates that it can cost as much as $500.

Therapy Options. Treatment of cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy varies depending on the individual case. If a cat has progressed to congestive heart failure, veterinarians usually prescribe a diuretic to remove excess fluid from the lungs and other body tissues. They may also give medications called angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, which may improve the heart’s ability to pump blood and may decrease the degree of thickening of the heart, although this is controversial.

A major goal in the treatment of HCM is to control the heart rate, which is commonly elevated in cats with the disease. One way to do this is to administer beta blockers. These drugs block the effects of the hormone norepinephrine, resulting in slower, less forceful heat beats. Studies investigating the effectiveness of beta blockers and of other classes of drugs in controlling the heart rate in cats with HCM are ongoing at several institutions.

Cats with HCM, including those who survive congestive heart failure, will likely be on medication for life. Veterinarians will often prescribe anticoagulant medications, including aspirin and/or clopidogrel (Plavix), to reduce the likelihood of blood clot formation in these patients.

“It’s important to understand that we’re not curing these cats,” Dr. Kornreich says. “Rather, we are managing their disease and decreasing the severity of their clinical signs.” One important clinical sign, or symptom, of HCM is an elevated respiratory rate. The veterinarian will often instruct owners to monitor their cat’s resting respiratory rate at home.

Monitoring Respiration. While guidelines vary slightly, healthy cats typically breathe between 20 and 30 times per minute. If owners notice the rate increasing — particularly a steady increase over the course of several days — it might warrant a call the veterinarian. If the respiratory rate rises over 40, it’s important to promptly contact a veterinarian.

The prognosis for cats with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy depends on the severity of symptoms. Some cats can live for years on medications to control the condition. However, those who go into congestive heart failure and/or develop blood clots have a more guarded outlook.

The challenge for owners and veterinarians alike is detecting feline heart conditions before they progress to congestive heart failure, and working together to optimally manage heart disease if and when it is diagnosed. With continued research into the mechanism of HCM and other cardiac diseases in cats, there is hope for improved prognosis and perhaps definitive curative therapy for these conditions in the future. ❖