Feline infectiousperitonitis ranks as one of the deadliest diseases affecting cats — it’s the leading cause of death in cats under 2 years of age. Veterinary scientists have long suspected that the FIP virus (FIPV) was a lethal mutation of the feline coronavirus (FECV), a benign and common intestinal virus, but they couldn’t identify how this transformation occurred.

288

Until now. By taking a novel approach to studying FIP — at the molecular level — a team of Cornell University researchers has identified the changes that happen when the coronavirus mutates into FIPV.

Possibility of Vaccines. This breakthrough is viewed as a vital first step toward accurately diagnosing FIP and eventually developing vaccines and treatments, says the study’s lead scientist, Gary R. Whittaker, Ph.D., a Professor of Virology in the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine’s Department of Microbiology and Immunology.

“For far too long, FIPV has been tricky to diagnose because there are two forms of the same virus: one is benign (FECV) and one is lethal (FIPV),” says Dr. Whittaker. “All current testing cannot discriminate because the two are quite similar. Until now, it was possible to say the virus is there, but we weren’t able to say if it was safe or dangerous.”

288

As a result, countless cats suspected of having the FIP virus have been euthanized in catteries and animal shelters to stop the spread of the virus. The only available vaccine is not generally recommended by the American Association of Feline Practitioners. And there is no known cure or effective treatment.

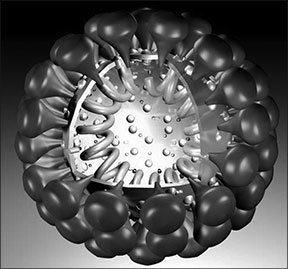

Dr. Whittaker’s team compiled hundreds of samples of feline coronarvirus from donations from veterinarians and cat owners. The samples included feces, blood and abdominal fluid. His decision to narrow his focus on a part of the virus’ structure — crowns of spikey proteins on coronavirus particles — led to the discovery.

He had long suspected that the proteins change shapes when responding to proteases — the enzymes that break down proteins — in white blood cells, Dr. Whittaker says. When he compared a site in the spike protein in the coronavirus to the same area in FIPV that was known to activate members of other virus families, including influenza, via a host cell protease, he found differences in the spikey proteins and the genes that code them. The benign coronavirus had mutated into lethal FIP.

Molecular Basis. “As a result of our research, we’ve found the first known molecular basis for FIP,” Dr. Whittaker says. The findings were published in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases. The Morris Animal Foundation, Winn Feline Foundation and Cornell’s Feline Health Center funded the research.

“FIP has taken the lives of so many cats and until now, we simply didn’t know much about how the common feline enteric coronavirus mutated into this deadly disease,” says David Haworth, DVM, Ph.D., president and CEO of the Morris Animal Foundation. “Thanks to Dr. Whittaker’s discovery, scientists may now be able to develop an effective vaccine and possible treatments for this terrible disease.”

288

Dr. Whittaker has been studying ways to combat FIP for more than two decades. “FIP is a tragic disease for families falling in love with new kittens and for veterinarians who can do nothing to stop it,” he says. “None of my personal cats have had FIP, but I have had far too many friends and colleagues who have had cats with FIP.”

Help for Shelters. His long-term goal is to develop an effective vaccine. “We have gained a lot of information based on our research, and now we can apply this and make better informed decisions. We are also hoping that we will be able to provide better information to shelters and breeders so that they will be better able to screen cats before they go to owners and prevent the spread of FIP.”

Dr. Whittaker regards FIP as one of the most challenging viruses to defeat but says this new discovery could spur advances in treating diseases in animals and people. “This is a scary virus from many standpoints, but this discovery could have implications for similar coronaviruses, such as FIPV’s deadly cousin in ferrets and another human-infecting cousin emerging from bats in the Middle East,” he says. “For now, it finally unlocks the door to developing the world’s first effective diagnostics, preventions and therapies for FIP in cats.” ❖