A neutered male Persian experiencing severe lower back pain had his owners concerned and his veterinarian puzzled. That prompted a referral to Cornell University Hospital for Animals, where the veterinary team turned to one of its most sophisticated diagnostic tools: magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

The images revealed that the nearly 2-year-old cat had a bone lesion compressing the spinal cord and causing pain, says radiologist Peter Scrivani, DVM, ACVR, Associate Professor of Imaging at Cornell. “MRI also showed that the type of bone lesion was consistent with a benign vascular malformation that would be cured if the abnormal bone were removed. Surgery was performed and the cat did well.”

Favorable Follow-Up

At his six-month recheck examination, the cat was normal and pain free. Another success story, thanks to MRI. Million-dollar-plus MRI machines are part of imaging methods now being used with increasing frequency in veterinary medicine. Other options include X-rays, computed tomography (CT), ultrasound and nuclear medicine. Cornell performs about 400 MRI examinations on dogs and 25 exams on cats annually.

“About 90 percent of the imaging caseload is radiology (X-rays) and ultrasound,” Dr. Scrivani says. “If, however, you want to image the brain or the spinal cord, you definitely want to go with the MRI. Also, for assessing certain types of back fractures or congenital anomalies, the CT might be a better option.”

It’s important to note that imaging methods are not in competition with each other. “They are complementary, and sometimes we may perform both MRIs and CTs to get the most information possible,” Dr. Scrivani says.

MRI is safe and doesn’t produce exposure to ionizing radiation like X-rays. “Extreme caution is taken to ensure that no one enters the MRI room with loose metal because if metal gets sucked into the MRI, it becomes a projectile,” Dr. Scrivani says. “Collars are removed, and we take radiographs in some animals to make sure they have not ingested any metal.”

Microchip identifications inside pets having MRIs will not cause harm, but Dr. Scrivani says sometimes these microchips do migrate in the body and can interfere when attempting to acquire images near the spine. “But this is an infrequent problem,” he says.

Costs Still High

Certainly, cost is an issue. Imaging averages $1,000 to $4,000 per session, including anesthesia. Many major pet insurance companies cover some or all the fee. The expense of the MRI machines and the required shielded rooms explain why they tend to be available only at specialty hospitals and some veterinary schools and not at general veterinary practices.

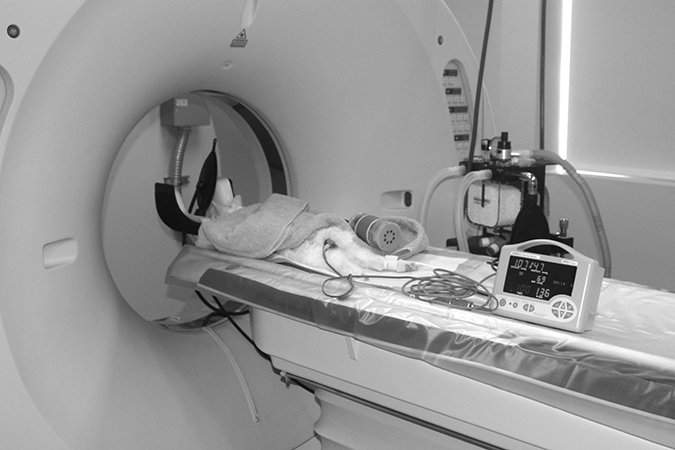

Cornell has a Toshiba Vantage Atlas 1.5 Tesla machine designed for human use and adapted for animals. It was installed in 2010 at a cost of about $3 million, including a CT scanner and needed room renovations, with most of its cost covered by a $2.125 million donation from Janet Swanson, the wife of Cornell alumnus John Swanson. The tube-like machine is “closed,” unlike the open machines sometimes used for human patients.

“With a closed machine, for the most part, we get a better signal and so usually get a better image,” Dr. Scrivani says. “In people, claustrophobia can be an issue, but all our patients are under anesthesia so that is not an issue.”

MRIs use magnetic waves up to 40,000 times stronger than the earth’s magnetic field to detect abnormalities. Cats being imaged are placed under general anesthesia so they remain motionless to avoid blurred images during imaging, which can take up to two hours. “It takes time to make an MRI image and patients must be still during this time to achieve the best image quality possible,” Dr. Scrivani says. “Plus, patients must remain in a particular location within the scanner where the best images are produced.”

Minute signals are generated as the cat’s body responds to the magnetic field. The signals are then converted to a cross-sectional image that enables radiologists and other specialists to look for signs of injury and disease. At Cornell, all data is digital and medical reports are available to referring veterinarians via computer access.

Looking Ahead

MRI’s use and precision are expected to expand even more. “The typical lifespan of a MRI scanner is about 10 years, so we will be looking for a means to replace or upgrade our system in the near future,” Dr. Scrivani says. “The scanner has been excellent, but we look forward to having access to innovative technologies that will improve our clinical, teaching and research programs, allowing us to offer novel imaging examinations.”

Improvements may include upgrading to a 3 Tesla MRI, a newer generation MRI that can provide even greater imaging details. Dr. Scrivani also anticipates:

Short examinations. “Often, there is a trade-off made between image quality and time to acquire the image. Faster examinations with improved image quality are a likely advancement.”

Improved molecular imaging to see how cells handle chemicals or drugs. “This is the future of MRI, but not in the near future for clinical practice,” he says.

A trend toward producing hybrid images — combining two methods like CT and positron emission tomography (PET scans), which uses small amounts of radioactive materials. The images could provide both structural and functional or molecular information in the same image.

Whatever the technological advances, Dr. Scrivani says veterinarians face challenges to keep on top of their game. “Modern imaging can produce exquisite depictions of patient morphology — the form and structure of organisms — but there still is a need for expert interpretation, technical expertise and continued research.”

Michael P. Connor

Which Imaging is Right for Your Cat?

These are some of the features of various imaging tools.

X-Rays: No Anesthesia Typically Needed

They can detect changes or abnormalities in bone and soft tissue based on absorption of electromagnetic radiation. They’re most commonly used to obtain images of the abdominal and chest cavity for signs of lung, heart or abdominal organ disease, as well as to identify bone fractures in cats showing signs of lameness.

Advantages: Most veterinary clinics can take X-rays without cats needing to be sedated or anesthetized. “Radiographs provide a quick and relatively inexpensive evaluation, which can be helpful following trauma such as a skull fracture,” says radiologist Peter V. Scrivani, DVM, ACVR, at Cornell.

Drawbacks: The images can’t distinguish between soft tissue or fluid, necessitating speculation or more precise imaging for a diagnosis. Care must be taken to prevent radiation exposure to technicians who operate the machine.

Cost: $50 to $100 per image.

Ultrasound: Real Time Results

Sound waves are transmitted and reflected back from targeted tissue. The non-invasive option allows veterinarians to view the heart, abdominal organs, muscles and tendons.

Advantages: Images are available in real time versus a snapshot from X-rays. They can detect differences in the density of tissue and fluids, can identify the presence of crystals in urine, and see blood flowing through the chambers of the heart and blood vessels.

Drawbacks: It can be time consuming if many organs are being examined. It doesn’t provide the detail of MRI.

Cost: $300 to $400.

Computed Tomography: Images in 3-D

The donut-shaped CT scanner uses sophisticated computer processing to create three-dimensional, cross-sectional images of the body. An X-ray shows only a flat, two-dimensional view.

Advantages: A CT can obtain a view of a body organ or tissue in less than an hour. It can detect trauma and head, lung and nasal diseases.

Cornell

Drawbacks: General anesthesia is usually required and the cat must remain still for several minutes inside the scanner. The scan cannot identify subtle changes in the body that an MRI can.

Cost: $500 to $1,200, plus the anesthesia fee.

Finding Defects from Brain Swelling to Joint Disease

MRIs can noninvasively identify health and medical problems, including:

Brain tumors

Brain swelling or inflammation

Traumatic brain injuries

Herniated, bulging or degenerated intervertebral discs in the spine

Stenosis (narrowing) of the spinal column

Spinal tumors and congenital abnormalities

Inflammation of the spinal cord or nerves

Infections of the spine

Joint diseases

Compression fractures

Nuclear Medicine Imaging: Limited Availability

Nuclear medicine imaging allows veterinarians to track internal hemorrhaging and kidney function. It can also aid in diagnosing stress fractures. At Cornell, it is rarely used except to diagnose hyperthyroidism in cats, the cause of lameness in horses and to rule out portosystemic shunts (abnormal blood vessels that bypass the liver) in dogs.

Regulations regarding radioactive pharmaceuticals can limit their availability. Their use must be documented and the veterinary patient remains hospitalized while the pharmaceuticals are mostly cleared from the body.

The imaging involves administering a small amount of a gamma ray-emitting radioisotope to a sedated patient. A camera device then detects the location and distribution of the radioisotope.

Veterinarians watch how organs process these “tagged” medicines. The study shows how an organ or body system functions, not simply its appearance. The cost is usually $400 to $600.