Fever, lethargy, loss of appetite and evidence of painful stiffness in the muscles and joints are clinical signs of many ailments that can afflict your cat at any time of year. Some feline disorders, however, are more prevalent during warm weather, when higher temperatures stimulate the activity of disease-causing organisms and the parasites that can transmit them to your cat. Bev Caldwell 288 One such condition is Lyme disease, a potentially severe bacterial infection that, if untreated, can progress to extensive joint damage and potentially deadly cardiac complications, kidney failure and neurologic dysfunction. The disease, which is named after the town, Old Lyme, Connecticut, where it was first identified in 1975, is most frequently diagnosed in the Northeast, but it has been reported in all 48 states of the contiguous U.S. Feeding on Blood

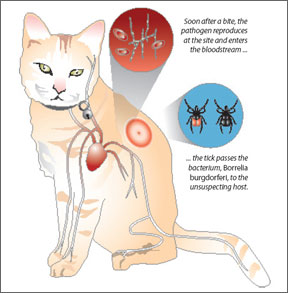

Lyme disease is caused by a spiral-shaped bacterium called Borrelia burgdorferi, which enters an animals system via the bite of a young tick (nymph) or an adult female tick. In the northern, midwestern and southern areas of the nation, infection is transmitted primarily by the black-legged tick, otherwise known as the deer tick. On the West Coast, the bacterium is generally carried by a similar parasite, the western black-legged tick.

Ingestion of blood is necessary for the ticks life cycle, which is launched in the late spring and early summer. During that period, the female tick lays eggs on the ground, from which countless minute larvae soon emerge, all of them eager and well equipped to crawl onto a passing animal. A deer ticks preferred host at this initial stage is the white-footed mouse, which is known to be a natural carrier of B. burgdorferi. (In the West, the ticks preferred natural host is a lizard or other reptile.) As they feed on the infected mouse or reptiles blood, the larvae ingest the bacteria. After a few days, they drop off the host and transition into the next stage of their metamorphosis, during which the bacterium-infected larvae shed their outer coats to become nymphs. Then, following yet another blood meal, they mature into adults and settle in for a long winters nap.

A Second Round

When warm weather returns in spring, the mature ticks become active once again and resume their quest for a blood meal, which females need in order to complete the life cycle by mating and

288

laying eggs. And as they feed this time, the parasites infect their new hosts – cats as well as humans, dogs, horses and other animals – with the dangerous bacteria that they have harbored since their larval stage.

Ticks do not hop like fleas. Rather, they crawl, and the parasites – having four pairs of legs in their nymphal and adult stages – are very good at it. They perch on the top ends of grasses and other vegetation and await the approach of a host, sensing its arrival by the vibrations of a footfall or a sudden change in temperature caused by the potential victims body heat.

Immediately after a tick attaches itself to its host, the bacteria begin to reproduce in the area surrounding the bite. Soon afterward, the pathogens move into the bloodstream, and the early signs of Lyme disease will usually become evident within four weeks of infection.

Prompt Treatment

Immediate veterinary consultation is warranted if any of the typical signs – fever, lethargy, poor appetite, swollen joints, lameness, swollen lymph nodes – are observed during “tick season.” Lyme disease can be diagnosed through a variety of laboratory tests, including sophisticated blood analyses, with treatment usually involving the use of an antibiotic. In general, cats that are treated promptly have a very good chance of full recovery.

If infection is diagnosed and treated in its earliest stage, relief of pain and lameness can be achieved within a day or so; if treatment is somewhat delayed, relief may take considerably longer and may require prolonged treatment. But an infection that remains untreated for an extended period can result in irreversible tissue damage.

Although a vaccine is available to protect dogs against Lyme disease, no such vaccine has been developed for cats. However, a cat can be protected to an extent during warm weather by spraying it with an insect repellent before it goes outdoors. And its coat should be brushed and thoroughly examined for ticks when it comes back inside. If a tick is spotted, it should be removed, totally if possible, using a fine-tipped forceps or a tweezer that reaches beneath the parasites body and grabs it by its head.

Since a female may be carrying eggs, it is advisable to drop the tick into a bottle of alcohol and seal the bottle tightly. If it is not possible to remove the entire tick, an antibiotic ointment should be applied to the area of the bite and the cat should be taken to a veterinary clinic for examination.

v