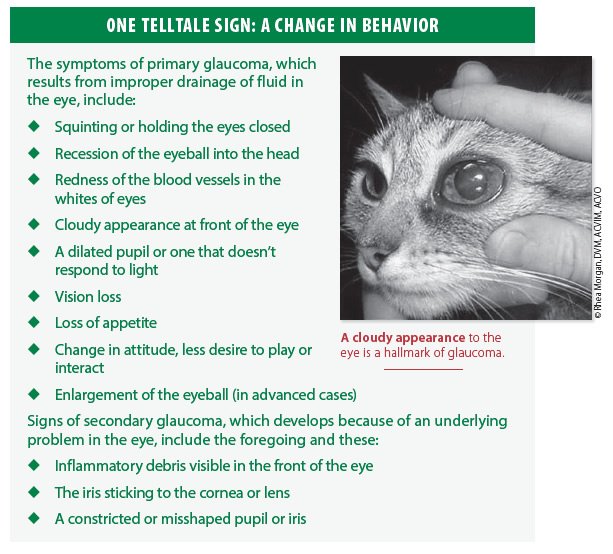

If your cat squints or his eyes are increasingly tearing, take a closer look. Does he have a red eye with a cloudy blue tint to the surface and a dilated pupil? These could be signs of glaucoma that require immediate treatment to avoid significant or complete loss of vision. Because of the subtle nature of the symptoms, some cats don’t have a veterinary examination until substantial damage has occurred.

The challenge for owners is early recognition of symptoms. “Sometimes the signs of glaucoma can be very vague, such as the cat sleeping more or acting a little head shy when you go to pet him on the top of the head,” says ophthalmologist Kenneth Pierce, DVM, MS, ACVO, at Cornell University Veterinary Specialists in Stamford, Conn.

Like a Headache. Pain can cause a cat to be wary of petting. “I typically tell owners the pain associated with glaucoma is like having a constant headache,” Dr. Pierce says. “You can still function, but your head hurts. Some cats may show only some of the signs.”

Nevertheless, glaucoma is a medical emergency. “Quick identification and presentation to the veterinarian or an ophthalmologist may save your cat’s vision or eye,” Dr. Pierce says.

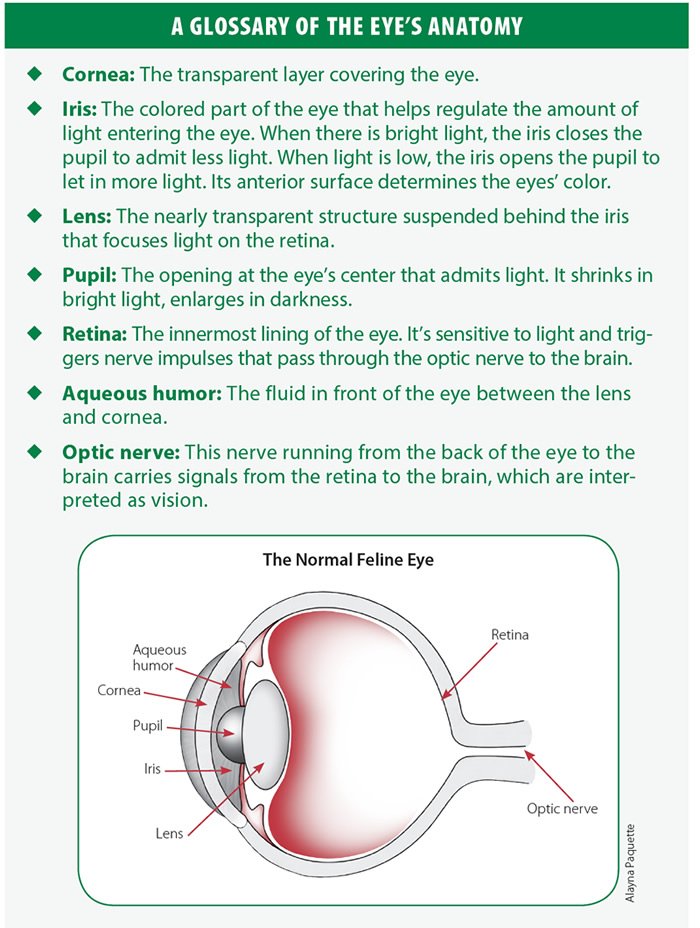

Glaucoma develops when a watery fluid called the aqueous humor in the front of the eye is unable to drain correctly. The fluid builds up within the eye and puts pressure on the retina and optic nerve leading from the eye to the brain. If the condition progresses without treatment, it is likely to result in permanent total blindness.

Glaucoma can be primary, resulting from a buildup of fluid, or secondary, occurring when other problems exist. Primary glaucoma in cats is less common and thought to be inherited. Burmese, Persian, Siamese and domestic shorthair cats are among the predisposed breeds.

Symptoms can begin early in life or may not be present until cats are middle-aged and older. A cat with primary glaucoma will inevitably develop the condition in both eyes, which is known as bilateral glaucoma.

Secondary, or acquired, glaucoma is estimated to represent 95 to 98 percent of glaucoma cases in cats. It can develop in one or both eyes, and isn’t believed to be inherited. The most common cause is uveitis (inflammation of the uvea, a pigmented layer of cells in the eye), which tends to affect cats middle-aged and older. This severe eye inflammation causes changes within the eye that can result in blockage of the eye’s internal drainage system. It can occur after an infection by disease such as the feline immunodeficiency virus, feline leukemia virus, feline infectious peritonitis and the protozoal disease toxoplasmosis.

Other causes of secondary glaucoma include cataracts, injuries, cancers within the eye and slippage of the lens known as luxation.

Severe Inflammation. “Early warning signs are difficult to identify in cats with primary glaucoma,” Dr. Pierce says. Luxation may cause severe eye inflammation, resulting in tearing or discharge from the eye, redness to the eye, and a constricted pupil.

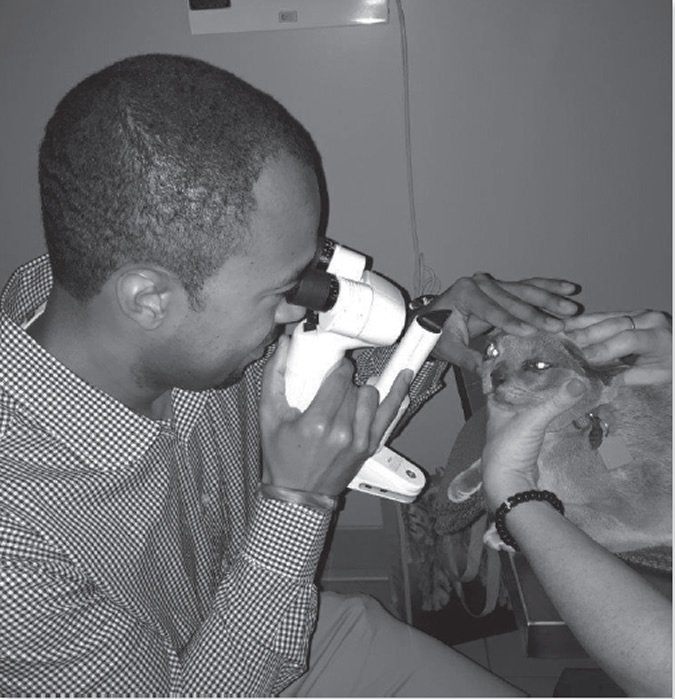

Veterinarians begin a diagnosis by taking a medical history, including signs and possible injuries — even minor ones. They will use a tonometer to measure the pressure within the cat’s eyes. “The tonometer is like a pen that measures the force required to indent a very small section of cornea,” Dr. Pierce says. “Cats with glaucoma will have a higher force measurement representing the pressure within the eye.” The cat is awake for the test, with the eye numbed by a topical anesthetic medication.

The next step may be a referral to an ophthalmologist for a more detailed examination. Specialty diagnostic tools include:

Gonioscopy to help determine the remaining eye’s predisposition to developing glaucoma when primary glaucoma is present in the other eye. The test, performed while the cat is awake, involves placing a special contact lens on the eye to examine the drainage angle.

Electroretinography to test the extent of damage to the retina, the light-detecting portion of the eye. While the cat is under sedation or general anesthesia, an electrical sensor is placed on the eye to measure the electrical activity of the retina in response to a flash of light.

High-resolution ultrasonography to identify abnormalities within the drainage system within the eye.

Cats with glaucoma typically are managed medically. The veterinarian will prescribe multiple drugs to lower the pressure within the eye and return it to the normal range as quickly as possible to salvage vision. In cases where only one eye is affected, eye drops and pills that help decrease fluid production or increase fluid drainage from one or both eyes can help delay or halt glaucoma development in unaffected eyes.

For blind or painful eyes, the veterinarian might recommend complete removal of the eye. The empty socket can be permanently closed or filled with an orbital prosthetic for appearance’s sake. If blindness develops, most cats adjust well, especially if they’ve been losing their vision over a period of time.

The costs associated a specialist’s consultation and exam are usually slightly higher than at those with a primary veterinarian. Medication might cost $100 to $200 per month. “If surgery is required, fees vary based on the best surgery to make your animal comfortable and controlled long term, the surgeon (primary veterinarian vs. ophthalmologist), and the overall health status of your cat. The costs may be in the hundreds to thousand-dollar range,” Dr. Pierce says.

When glaucoma is identified early and the veterinarian is able to manage the condition, regular examinations will be needed to monitor the pressure within the eye. There is a risk for cats with primary glaucoma to develop complications in their unaffected eye within eight months.