Not sure if a cat you want to adopt or even approach is fearful or simply shy? Recognizing the difference between the two behaviors can mean the start of a trusting relationship or the onslaught of an attack.

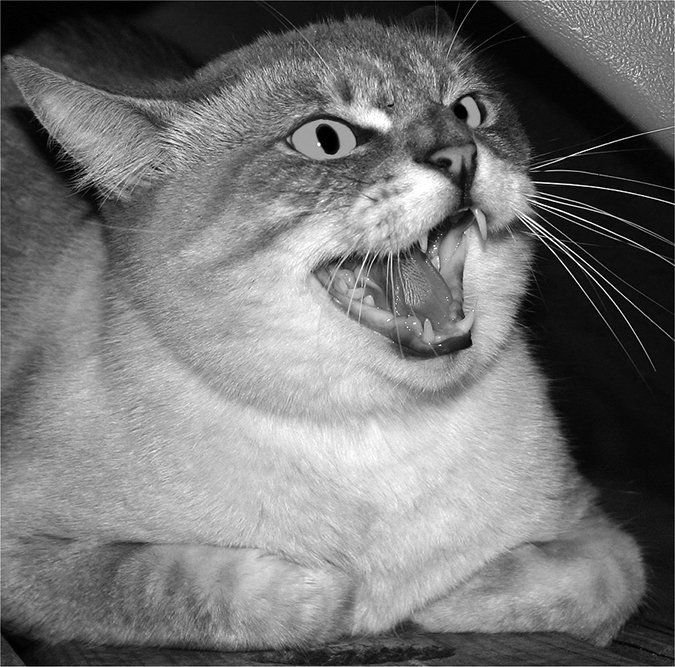

A shy cat is more apt to freeze in place and tremble in hopes that you will walk away. A fearful cat will likely flatten his ears, dilate his pupils and deliver a warning hiss before swatting or biting you if you try to touch him.

“There is no doubt that the behaviors exhibited by fearful and shy animals overlap,” says Leni Kaplan, MS, DVM, a lecturer in the Community Practice Service at Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine.

Feeling Threatened

ArtbyAllyson | Bigstock

“In my experience, shy cats will usually not show signs of aggression because they are trying to get away or avoid being the center of attention. Fearful cats, on the other hand, tend to feel threatened or endangered — whether it is genuine or imagined — and are likely to hiss or growl to discourage being handled.”

Other signs of fear include a cat bringing his feet closer to his body, lowering his head and making himself seem smaller. He may arch his back and flatten his ears even more when a stranger approaches.

“The breeds most fearful of strange people are Abyssinians and Persians,” says behaviorist Katherine Houpt, VMD, Ph.D., professor emeritus at Cornell. “The ideal window for socialization is 2 to 7 weeks. A kitten should be handled by people before weaning, but some cats are genetically fearful and socialization will not make them non-fearful.”

Dr. Kaplan adds that kittens learn social and hunting skills from their mother and siblings between 6 and 8 weeks of age. “It is best to adopt kittens after 10 to 12 weeks of age so they have had a chance to socially develop. They will usually acclimate to a new home more easily at this older age.”

Predator and Prey

Yastremska | Bigstock

Unlike dogs, cats are solitary hunters by nature and are apt to avoid a fight or conflict whenever possible by distancing themselves and hiding or fleeing. As both predator and prey, cats often show fear or defensiveness in strange surroundings or with unfamiliar people. If they perceive they’re being cornered, they may lash out.

In a 2013 study conducted by Maddie’s Institute under the direction of behaviorist Sheila D’Arpino, DVM, a kitten’s or cat’s behavior in a shelter is not always an accurate representation of his behavior when he enters a less stressful surrounding, such as a home.

The study found that 87 percent of respondents (1,069 individuals) reported that a shy or fearful cat they adopted or fostered hid for the first 24 hours. More than half — 55 percent — reported that they were able to interact within two weeks, and most became comfortable and relaxed in less than three months.

The conclusion: Many shy or fearful cats can evolve into loving pets if owners properly handle them, use behavior modifications and/or anti-anxiety medications, and provide a safe environment. “Make sure the cat has escape routes like on top or under furniture, especially if there are dogs or other cats in the home,” says Dr. Houpt. “Initially, keep dogs on leashes inside or at least separate them in a different room using barriers, such as baby gates, so they can sniff one another without having close or physical contact.”

Dr. Kaplan encourages owners to be in tune with their cat’s individual temperament and work within his limits. Some cats may simply prefer less handling and attention. The experts’ advice to help a shy or fearful cat feel more comfortable:

1. Limit exposure to situations that create fear and anxiety. For example, feed the cat in a separate room. He needs to feel that he can eat without being threatened.

2. Consider clicker training to teach him new tricks and build confidence. Predictability also helps build confidence and a sense of security. Cats are fans of routine.

3. Create a calm, stable environment by offering cat trees and litter boxes in different locations.

4. Limit handling the cat initially and slowly build his trust in you. “I’m a strong advocate of low-stress handling techniques,” says Dr. Kaplan. “I use towels or large blankets to handle cats. Usually they do not fight or flail because they are not being directly touched by the person restraining them. Do not scruff cats because this will only escalate their fear, anxiety and shyness so that they will no longer be able to be handled.”

5. When visitors arrive, “Do not drag the cat out to meet them,” Dr. Houpt says. “Show them the cute pictures on your phone instead.” Dr. Kaplan recommends letting cats direct the interaction and approach the visitor on their own terms.

Recognize that your cat tunes into your emotional state and can sense when you’re impatient or afraid. When taking your cat to the veterinary clinic, for example, try to reduce outward displays of fear or anxiety.

Also, understand that the source of your cat’s fearful response may be an underlying medical condition, such as pain or hormonal imbalances. Book a veterinary appointment for an exam and ask if your cat may be a candidate for a sedative or anti-anxiety medication to be given before an anticipated stressful situation, says Dr. Kaplan.

Keep in mind that fear ranks as the most common cause of aggression in cats at veterinary practices, according to the American Association of Feline Practitioners. It’s critical to take measures to reduce or prevent the fear from escalating. For instance, the use of nylon face muzzles that cover the eyes calms some cats because it reduces the intensity of visual stimuli in the exam room.

Use Your ‘Library’ Voice in Greetings

Jagodka | Bigstock

When in doubt about a cat’s emotional state, Leni Kaplan, MS, DVM, at Cornell cautions that you should never:

– Attempt to invade his personal space.

– Lower yourself to be face-to-face.

– Touch his rear, tail or paw pads.

– Move abruptly or use large gestures.

– Speak in a loud voice.

The best way to greet a cat: Let him make the decision about whether he’d like to meet you, Dr. Kaplan says. “Do not approach the cat. Allow the cat to come to you. You can kneel down to the cat’s level and gently extend one finger or your hand.”

“I tell people that cats like quiet people,” says behaviorist Katherine Houpt, VMD, Ph.D., at Cornell. “When meeting a cat, use your ‘library’ voice.”

Reducing the Fear Factor in Vet Visits

All cats need a veterinary exam at least once a year, ideally twice. Marty Becker, DVM, a frequent TV guest expert on pets and best-selling author, is spearheading a national Fear-Free Initiative that includes veterinarians, animal behaviorists and other pet professionals.

The campaign identifies these steps toward achieving fear-free veterinary visits:

– Deliver a calm pet to the clinic by making sure the cat is safely inside a carrier. When at home, leave the carrier open in your living room to provide a comfortable, resting place.

– Limit food intake beforehand. Some cats may respond favorably to receiving a favorite treat during the appointment.

– Call ahead and request that your fearful cat be allowed to go directly into an exam room rather than wait in the waiting area.

– Seek clinics that may incorporate pheromones, calming music and a silent space heater to keep the exam room feel safe.

– Take a bath towel to place on the stainless steel exam table to avoid your cat’s slipping.

– Allow the cat time to explore the room to get used to the environment before the exam begins.

– Ask about options to administer vaccines, such as small-gauge needles or a reduced dose. Also, ask about warming injections to room temperature — as long as this doesn’t impact the product’s effectiveness.

Best Carrier

The type of pet carrier you select can also help mitigate some fearfulness at the clinic. Plastic carriers with removable tops and fronts can allow a fearful cat to remain in the carrier during an examination. By allowing the cat to say in the bottom half of the carrier, a towel can be placed over him creating a “tent effect” but still allowing access.

When returning home, reduce the risk of aggression from your other cat or cats by leaving him in the carrier. Watch how the other cat(s) react to hm. “The cat who is returning may be perceived as being different — perhaps because of areas of shaved hair after a procedure — or a smell,” Dr. Kaplan says. The cat may have hospital scents on him, putting the other cats on the defense. They may act as though the returning cat is a stranger.

You may have to wait several hours before letting your cat out of the carrier. Wait for any hissing from the other cats to subside. If signs of aggression surface, distract the cats by clapping or stomping to separate them. Never attempt to physically separate them or pick one up when they’re in an aroused state. One or both may redirect their aggression toward you.

Dr. Kaplan’s parting advice: While some cats, no matter the time and energy devoted to them, will not acclimate to a given household, it’s possible for many cats, with their owners’ patience and training, to allow the human-animal bond to thrive.