Ear infections are relatively uncommon in cats — infections of the external ear occur twice as often in dogs. However, you should be aware of these significant facts: A study shows that geography can determine if your cat is likely to develop an ear infection. Left untreated, an infection can become chronic, causing pain and irreparable damage to the ear canal or eardrum.

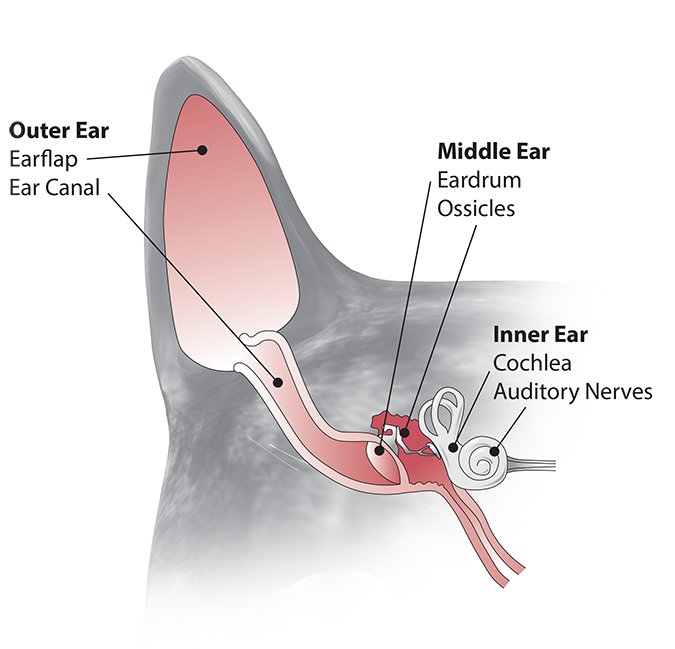

“Beyond the discomfort the animal experiences, the infection can extend beyond the external ear canal,” says dermatologist William H. Miller, VMD, one of the medical directors of the Cornell Companion Animal Hospital. “It can also spread into the middle and inner ear and cause neurologic signs and deafness.”

At-Home Ear Infection Test

You can become the first line of defense in identifying an ear infection. Simply check your cat’s ears by giving them a quick rub — something you probably do everyday. Whether your cat shows pleasure or discomfort is a clue to the ears’ condition. “If there is pain or if the animal really gets into it and rubs the ears against your hand, they probably have a problem,” Dr. Miller says.

For a closer inspection, give the ears a good sniff. They should not have an odor. Look inside. Normal, healthy ears have a nice pale-pink or grayish color. Redness, especially if the tissue also appears swollen, signals inflammation or infection. Anytime your cat shows these signs, he needs to see the veterinarian. At-home treatment with eardrops may be useless or even counterproductive if the medication is aimed at the wrong agent. In treatment, veterinarians prescribe medications specific to the type of infection.

About that geographical risk: In its State of Pet Health Report 2016, Banfield Pet Hospital, with 900 locations in the U.S., found a higher incidence of feline ear infections in Kentucky, Florida, Indiana, Ohio and the territory of Puerto Rico.

Clean Your Cats’ Ears Only When They’re Dirty

© Cherry-Merry | Bigstock

Most cats’ ears remain healthy when you follow this simple advice: Clean them only if they look dirty. “The normal ear comes with its own built-in ear-cleaning mechanisms,” says dermatologist William H. Miller, VMD, at Cornell. “If ear cleaners are used when they aren’t needed, they can damage the normal cleaning mechanisms.”

The frequency of cleaning the ears varies from cat to cat. These are the basics:

– Clean ears as directed by the veterinarian if your cat has an active ear infection or is recovering from an ear infection or injury.

– When necessary, use a mild cleanser made for cats such as Oti-Clens, available from veterinarians and pet supply stores, or another cleaning solution the veterinarian recommends.

– Never clean ears with alcohol. It can sting or dry delicate ear tissue.

– You can use a cotton-tipped applicator to clean the folds and creases near the surface of the ear, but don’t insert it into the ear canal. That pushes wax deeper inside.

– Clean the ears using one hand to tilt the cat’s head downward. With the other hand, squirt enough cleanser into the ear to fill it. Gently massage the outer part of the ear to move the fluid into the ear canal so it can loosen any dirt and debris inside.

When you’re finished, stand back and let your cat shake his head. That helps remove the debris. Finally, wipe the ear with a cotton ball to remove any excess cleanser as well as any debris the cat shakes loose.

The Amazing Anatomy of Cat Ears

A cat’s ears are one of his most important anatomical features. They’re able to move forward, backward and sideways, and help him hear the faintest sound — an invaluable ability for an animal that is both predator and prey.

Their hearing far surpasses ours. “While the human auditory system is capable of detecting sounds ranging in frequency up to about 20,000 vibrations per second, cats typically can sense sounds pulsating at 60,000 vibrations per second or greater,” says the Cornell Feline Health Center, adding that this sensitivity has been honed over the ages to alert to the stealthy approach of a dangerous predator or detect the underground movement of a burrowing rodent.

Marty Bee

Underlying Issues

“We aren’t certain why these are the states with the highest prevalence, but pets usually get ear infections because of an underlying issue,” says Kirk Breuninger, VMD, MPH, with the Banfield Applied Research & Knowledge team called BARK.

© Life on White | Bigstock

Possible reasons for a geographic uptick in feline ear infections may include climate and local vegetation, Dr. Miller says. For instance, he says heat and humidity can alter the flora in the ear canal. “This doesn’t cause the ear infection but makes it easier for an infection to occur when there is minor trauma to the ear canal.”

Banfield’s report found the prevalence of otitis externa, or inflammation of the external ear, to be 6.6 cases per 100 cats — unchanged in the past five years. (Canine infections totaled 12.9 cases per 100 dogs.) Otitis media is inflammation of the middle ear, and otitis interna is inflammation of the inner ear. Infections of the middle ear usually result from infection that has spread from the outer ear canal. Signs of both external and middle ear infections can be similar.

Cats who scratch their ears can cause abrasions and scabs, and may be suffering from drug, environmental or food allergies. Ingredients often linked to their allergies include beef, seafood, lamb, corn, soy, dairy products, wheat, chicken, eggs and pork.

Some lines of pedigreed cats have a higher incidence of allergies, Dr. Miller says. Himalayans, Persians and Abyssinians seem especially vulnerable. Cats seen at Banfield clinics for ear infections of all kinds are usually domestic shorthairs or longhairs.

Ear mites are a common culprit in ear infections, especially among kittens. The tiny parasites set up residence inside the ears and breed. Cats can be hosts to mites yet show few signs. “If there are no signs of ear disease, the queen’s ears won’t be treated and the mites will infest her kittens,” Dr. Miller says. “Since cats can cluster in large numbers and are often very social, the infected one can infect the whole group.”

© dolgachov | Bigstock

A sure sign of ear mite infestation: a dry, crumbly, dark-brown “coffee-ground” discharge. Other causes of ear infections include:

1. Abscesses in the ears from bite wounds when outdoor cats get into fights with each other

2. Overzealous cleaning — see above.

3. Ticks

4. Tumors or polyps

5. Yeast or bacterial infections. “They can take hold any time the ecology of the ears changes,” Dr. Miller says.

6. Foreign objects, such as grass awns, also known as foxtails, lodged in the ear canal. Various barbed foxtails, primarily found in California and other areas west of the Mississippi, can also penetrate the skin, eyes, nose and throat.

7. Autoimmune diseases like pemphigus, which affects the skin.

By looking into the ear through an otoscope, your cat’s veterinarian can assess whether the ear is inflamed and to what degree, whether a foreign body is lodged in the ear or a tumor is present, and whether the eardrum is involved. A history and physical exam can help to determine the possibility of an allergy.

If the cause of an ear infection isn’t obvious, ear cytology — an examination of the discharge microscopically — may be necessary to find the presence of bacteria, yeast, mites or inflammatory cells. Culturing the sample to identify the specific organism usually isn’t necessary.

An exception is chronic infections, especially those caused by gram-negative bacteria — those normally found in the gastrointestinal tract. Cultures can be expensive, but most cases of otitis externa can be managed with topical treatments. Depending on the cause and severity of the infection, a thorough cleaning and a course of anti-fungal or antibiotic drops or ointment applied to ears are usually all that is needed to clear up the problem. It is very important to treat for as long as the cat’s veterinarian indicates. Relapses are common when the treatment is discontinued too soon.