We have all seen the news accounts: Way too many cats being removed from unsanitary conditions, unhealthy, malnourished, and matted. Reports of overpowering odors, and often, sadly, dead or dying cats and kittens. Clearly, the felines are the victims, but perhaps the person involved is, too.

“I can’t stress how important it is to recognize that animal hoarding, while also a crime, is a mental health issue. Helping the individual who is hoarding is just as important as helping the animals, and may prevent future animal suffering,” explains M. Erin Henry, VMD, DACVPM, assistant clinical professor, Maddie’s Shelter Medicine Program at Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine.

According to the Hoarding of Animals Research Consortium, hoarding occurs when an individual possesses more than the typical number of companion animals and is unable to provide minimal standards of nutrition, sanitation, shelter, and veterinary care, with this neglect often resulting in starvation, illness, and death. Often, the person denies being unable to provide care and the impact of this failure on the animals, the household, and human occupants of the dwelling.

The reality is that most hoarding cases start out with good intentions. The person involved  is willing to help foster or adopt cats that have problems such as infectious diseases, disabilities or injuries, chronic health conditions, or orphaned kittens who need round the clock care. According to the ASPCA, some animal hoarders try to set themselves up as a rescue facility.

is willing to help foster or adopt cats that have problems such as infectious diseases, disabilities or injuries, chronic health conditions, or orphaned kittens who need round the clock care. According to the ASPCA, some animal hoarders try to set themselves up as a rescue facility.

At first, all may be well. But then five cats increase to 10, then 15 or 20 or more. Most individuals simply do not have the time, space, or financial capability to provide proper care for that many cats. The hoarders will defend themselves, saying that if they had not taken the cats in, they would have died or been killed. They feel that only they can provide these cats with what they need.

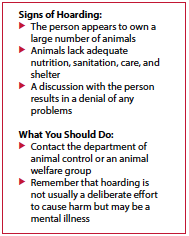

Recognizing an animal hoarder is not a simple thing. Usually, according to the ASPCA, the home is in disrepair; there may be a strong urine/ammonia smell; the individual is usually in a state of neglect; he or she doesn’t know how many animals are in the home; the animals are usually parasite-ridden, emaciated, poorly socialized, and often ill. The person will often deny that there is any problem.

What can you do if you suspect there is a hoarding situation? “It truly depends on how well you know the person, but I think the most helpful thing you can do in this situation is to contact the local humane law enforcement group (whether it is associated with the police department, animal control, or an animal welfare group),” says Dr. Henry. “They will be able to investigate further, and hopefully get both the animals and their caretaker the help that they need. If it is a family member, approaching the person may be an option.”

Remember that the hoarder does not feel they are doing anything wrong and may not appreciate your intervention. Getting an outside, objective agency involved tends to be the best option for all concerned. Caring for the person is equally as important as caring for the animals they are trying to help. Simply seizing the animals is like treating symptoms but not addressing the cause of a disease.

In Dr. Henry’s experience, and in reviewing many hoarding-case reports over the years, without appropriate intervention that focuses on animal hoarding as a psychiatric condition, various studies report a recidivism rate—the tendency to “re-offend”—of 60% to 100%. There have been no studies looking at the “relapse rate,” which is the tendency of those who have been “treated” for their condition to resume hoarding.

Anecdotally, however, the greatest level of success occurs in communities with a hoarding task force/alliance, which is when many different organizations (law enforcement, social work/human services, fire dept, animal services, etc.) work together to help the individual and the animals. This is likely because these communities are addressing the underlying problem that leads to hoarding.

If you suspect hoarding, don’t hesitate to speak up and follow through to be sure both the cats and people involved all receive the care and attention they need.