Your arthritic cat walks stiffly, and it’s difficult to find a medication to treat him without side effects. Could stem cell therapy be an option? Its use in human medicine has grown in the past decade, heralded as a promising treatment for a host of diseases. The latest area of pioneering research, according to the National Institutes of Health, is adult-derived stem cells for repair of the heart.

While stem cell therapy in dogs and horses has also increased, its use in cats has been limited for several reasons — principally the lack of research and its cost running into four figures.

Therapeutic Tool

We are working very hard to make stem cell therapy become one of our therapeutic tools,” says surgeon and orthopedic scientist Kei Hayashi, DVM, Ph.D., ACVS, at Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. “We just need to be careful and think what is best for our patients. There is no reliable data in cats” to prove the therapies work.

Chris Frye, DVM, a resident in both sports medicine and clinical nutrition at Cornell University Hospital for Animals’ Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation Service, is among those who want more hard science

about stem cells. “I’m eager to get some of the clinical trials done and get more data on how, where and when to use them. Stem cells are an exciting new frontier of medicine, as they may help mediate healing and potentially regenerate tissue.”

While some private practitioners offer stem cell therapy, many veterinary teaching hospitals consider it experimental. Cornell treats dogs and horses with stem cells. It has not treated cats.

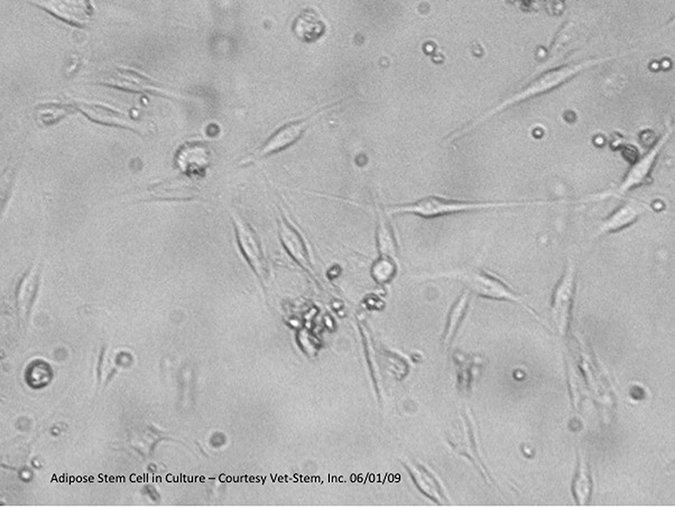

VetStem Biopharma

Limited Opportunities

Joseph Wakshlag, DVM, Ph.D., certified by the American College of Veterinary Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation Service, and chief of the Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation Service at Cornell explains: “The big difference between dogs and cats is that the typical cat is not as active as the typical dog, and we don’t recognize the joint problems with aging like we do in our dogs. So the opportunities to do stem cell therapy or regenerative medicine do not present themselves as often. From a fiscal perspective, companies interested in these technologies are not focusing on cats.”

Advocates point out the therapy is relatively non-invasive and safe. One downside is that it sometimes needs to be repeated. The therapy uses a cat’s own stem cells — typically derived from fat — to treat arthritis and renal problems. Studies are exploring it as a treatment for feline gastrointestinal problems and chronic kidney disease.

More than 11,000 animals in the past dozen years — mainly horses and dogs — have been treated for joint, ligament or tendon problems, according to VetStem Biopharma, a company in Poway, Calif., which processes stem cells.

CEO Bob Harman, DVM, says 200 cats have been treated via his company’s services — most for renal disease and about 50 cats for osteoarthritis. (His company is co-sponsoring a feline renal study at the Animal Medical Center of New York; some cats didn’t meet the strict study requirements, and their owners opted to treat them privately.) He suspects the small number of cats treated for arthritis is due to their pain going unnoticed by owners since cats “hide” their discomfort much more often than dogs.

VetStem Biopharma

Dr. Frye hasn’t yet treated a cat with the therapy but has done so for dogs — including one who had been unable to stand.

“The owners perceived a positive response to stem cell hip injections that included a better ability to get up, more eagerness to exercise and a greater endurance. The effect seemed to last about six months.”

Stem cell therapy is not a cure, cautions surgeon Lisa Fortier, DVM, Ph.D., who researches it in horses at her laboratory at Cornell. If a pet has arthritis, she says, “Stem cells will help but you can’t forget the basic things of good nutrition, weight loss and exercise. They aren’t going to override the tenets of good health. People often think, oh, this is the cure — and then you forget all the other really important foundation things you need to do to keep animals and humans healthy.”

Here are the basics you need to know about stem cell therapy:

What is the process for a cat?

Veterinarians remove a small sample of fat from the anesthetized patient and ship it overnight for processing at a university or, more commonly, VetStem, the first commercial company to offer the service to veterinarians. VetStem processes the fat to concentrate the stem cells. The pet is anesthetized again and the veterinarian injects the pet’s processed cells within 48 hours.

Cornell plans to develop its own system for processing. The collection and administration of fat cells for feline and canine patients could then be done at the same time. Pets would undergo anesthesia once and the single procedure would be less expensive.

Cornell

Is the treatment effective?

Only a few small studies have been done. An example: Ten cats with a form of chronic oral disease called gingivostomatitis didn’t improve with prior treatments such as full-mouth extractions and antibiotics, but “a number had complete cures” after two treatments of stem cells, according to a study at University of California-Davis published in January in the journal Stem Cells Translational Medicine.

In another study, seven cats with inflammatory bowel disease, whose symptoms included diarrhea and vomiting, underwent two treatments of fat-derived stem cells in a pilot study at Colorado State University. Five of the cats “improved markedly.” The results are promising, yet “much remains to be done before we would recommend stem cell therapy as the ‘go to’ therapy in cats with inflammatory bowel disease,” says researcher Craig Webb, DVM, Ph.D, ACVIM, at Colorado State.

In addition, the cost for a cat could be as much as several thousand dollars, which is clearly cost-prohibitive for most owners, Dr. Webb says. “The laboratory expertise, effort and expense behind this sort of therapy are huge, which can be hard for owners to appreciate when all they see is a simple injection.”

Chances are that stem cell treatments will need to be repeated several months or maybe years later, but at a fraction of the original cost since some of the pet’s stem cells will have been banked.

Why hasn’t the therapy proved effective for arthritis?

Cornell

“Many arthritis cases are due to an animal’s congenital or developmental condition, which results in mechanical abnormality,” Dr. Hayashi says. “An overwhelming, mechanically harsh environment [such as an orthopedic problem] negates the wonderful biological benefit of stem cells.”

He adds, however, that, “Stem cells may quiet down inflammation and pain. Stem cells need to be combined with other therapeutic options to be effective.”

Who are the best candidates for therapy?

Cats should be in good general health. VetStem rules out pets with cancer or systemic infection. Research has yet to determine the ideal patient, injury, dosage and frequency of treatment, says Dr. Frye; however, some published studies in the veterinary literature show promise for osteoarthritis or chronic muscle-tendon injury.

Why is the cost so high?

A reliable commercial service can charge $3,000 to $5,000 for processing, depending on the request, Dr. Hayashi says. “In addition, you need to surgically harvest a large amount of fat tissue under general anesthesia, which can cost $1,000 to $2,000.”

What does the future hold for cats?

Dr. Webb of CSU is concerned that while researchers are still trying to determine the efficacy of stem cells, they’re readily available online and from private practitioners. “There are major changes in the FDA regulation of stem cell therapy taking place as we speak that will hopefully positively impact the oversight of stem cell therapy in the veterinary — and human — patient population.”

Vicki L. Thayer, DVM, ABVP, executive director of the Winn Feline Foundation, which funds studies of stem cell therapies in cats, says more will undergo the therapy as marketing targets them and research proves whether they help such inflammatory conditions as IBD, kidney disease and chronic gingivostomatitis.