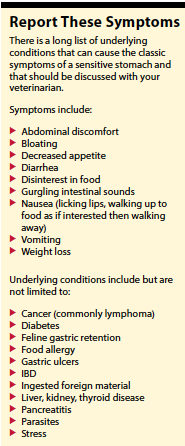

So, your cat has a sensitive stomach. What exactly does that mean? Frequent vomiting? Disinterest in food? Diarrhea? All of the above? The most important question is why. Before giving this uncomfortable situation the simple, benign-sounding moniker of “sensitive stomach,” it’s important to rule out any underlying medical conditions that could have serious, long-term ramifications.

First, if you have a cat that vomits, you should know that occasional vomiting is considered normal in the feline species, but the key is “occasional.” Vomiting more than once every few months is more than occasional and may be indicative of a medical problem.

Gary Norsworthy, DVM, a highly respected feline specialist in San Antonio, Texas, published a study in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association on small bowel disease in cats. Of the 100 cats in the 2013 study, 73 cats had chronic vomiting.

After the study, Dr. Norsworthy and his colleagues determined that both veterinarians and cat owners made excuses for chronic vomiting, such as sensitive stomach, hairballs, or eating too quickly, he said in Veterinary Practice News. He stated: “I am convinced that the vomiting of hairballs is a sign of chronic small bowel disease if it occurs twice a month or more in any cat; or if it occurs once every two months or more in shorthaired cats; or if it occurs in cats that are not fastidious groomers.” He urged veterinarians to be more proactive in evaluating cats, so they can get a diagnosis and treat cats appropriately.

Second, hairballs may be more than just hairballs. Current thinking on hairballs is that an underlying disorder, like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), may be interfering with normal gastric motility and that may be why the hair accumulates in the stomach.

Diagnostics

The gold standard of care for cats with a sensitive stomach starts with a comprehensive medical work-up including bloodwork [complete blood count (CBC), chemistry screen, thyroid hormone, fecal exam for parasites, and abdomen x-rays and ultrasound.

A stepwise approach to the diagnostic process is sometimes elected due to the expense associated with a comprehensive approach. Your veterinarian will determine which tests are most important to prioritize for your cat, based on the history you provide and your cat’s physical exam findings.

If no underlying metabolic disorders are identified, such as kidney disease, diabetes, or thyroid problems, your cat may have a food allergy or feline gastric retention (delayed gastric emptying).

Food allergy commonly causes GI distress for cats. A diet trial is the best way to rule out a food allergy. While proteins are considered the most likely culprit in food, there are so many shared ingredients in commercial cat foods that simply trying a different brand with a different protein source is likely to lead to frustration and disappointment. And a lot of wasted food.

As such, diet trials are best conducted using either a limited ingredient diet (LID) or a hydrolyzed protein diet (HP). A strict diet trial must be conducted for 14 days before deciding whether a positive response is achieved or not.

Hill’s and Royal Canin make a slew of prescription LIDs to choose from, and there are over-the-counter brands of LIDs available now, too. The important thing is to look at the ingredient list, making sure there is only one protein source and one carbohydrate source. The rest should be primarily vitamins and minerals. A novel (meaning that it’s new to your cat) protein source is best, like duck or rabbit.

Proteins are very large particles made up of amino acids. With food allergy, it is thought that the immune system sees these large particles as foreign invaders and tries to fight them. With HP diets, the protein source is broken down into smaller amino acid sequences, which are (hopefully) not recognized by the body as foreign. No foreign offender, no allergic response.

HP diets are available with a prescription, so you will need veterinary involvement. There are several products to choose from including Hill’s z/d, Royal Canin HP, Royal Canin Ultamino, and Purina HA.

Feline gastric retention is a gastric motility disorder that is defined by delayed emptying of stomach contents. Normal stomach emptying after a meal in cats is generally takes about four to six hours, with an occasional normal outlier at 10 to 12 hours. Cats that vomit partially digested food eight to 12 hours after a meal may well be suffering from feline gastric retention.

Inflammatory bowel disease and GI lymphoma commonly cause vomiting in cats, and the only definitive way to diagnose these conditions is by obtaining a biopsy of the intestinal tract, either via endoscopy or abdominal surgery, both of which require general anesthesia.

Endocrine diseases like hyperthyroidism and diabetes also can cause vomiting in cats, and these can be specifically treated if they are identified.

Try These at Home

First, small meals more frequently throughout the day will work better for these cats than a couple of large meals. Cat digestive organs are designed more for eating this way (think of cats hunting small prey in the wild).

For cats that seemingly eat too fast, spreading their food out on a dinner plate or on a cookie sheet will effectively slow them down.

If your cat does better with canned food than dry, feed canned. And vice versa. Although canned food is generally considered easier to digest.

Fats are harder to digest and may contribute to delayed gastric emptying. Choosing a prescription low-fat, highly digestible food like Hill’s I/d, Royal Canin GI, or Purina EN may help.

Medications

Talk to your veterinarian about whether medications might help. Drugs that promote gastric motility (prokinetics) relax the outlet to the stomach and encourage stronger contractions to move food along.

Metoclopramide and cisapride are examples of prokinetic drugs. The downside with these is they generally must be given three times daily, 30 minutes before a meal, which can be challenging, especially long-term.

Sometimes reducing stomach acid can settle a sensitive stomach. Famotidine (Pepcid-AC) is a popular H2 blocker that decreases the amount of stomach acid produced. It is commonly used on an extra-label basis in cats. It can be dosed once a day, which is nice. The downside is that cats seem to develop a tolerance to this medication over time, making it less appealing for long-term use.

Omeprazole (Prilosec) is a proton-pump inhibitor that also decreases the amount of stomach acid produced. It is also often used on an extra-label basis in cats, dosed twice a day, and is often a better choice for long-term use.

Your veterinarian may suggest trying a course of sucralfate, a medication that binds to irritated or ulcerated areas of the stomach lining, protecting it from further erosion by stomach acid, and allowing it to heal. The only way to know for sure whether ulcers are present is with endoscopy and/or biopsy, which are pretty aggressive, invasive procedures. Sometimes, response to therapy with sucralfate is a better way to back into a presumptive diagnosis of stomach ulcers.

Your veterinarian may suggest trying a course of sucralfate, a medication that binds to irritated or ulcerated areas of the stomach lining, protecting it from further erosion by stomach acid, and allowing it to heal. The only way to know for sure whether ulcers are present is with endoscopy and/or biopsy, which are pretty aggressive, invasive procedures. Sometimes, response to therapy with sucralfate is a better way to back into a presumptive diagnosis of stomach ulcers.

Because there is an abundance of serotonin receptors in the GI tract, fluoxetine (Prozac), a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) mostly used for anxiety and stress-related behavior, is thought to have a calming effect on the GI tracts of cats. Since stress in general can be a nemesis in cats, fluoxetine may well be worth a try.

In Conclusion

Here’s the bottom line on cats with sensitive stomachs. There are many possible underlying disorders that must first be ruled out before the gentle label of “sensitive stomach” can be applied to your cat.

If underlying diseases have been ruled out, don’t lose hope. There are things you can try, as described above, to help settle that sensitive stomach.