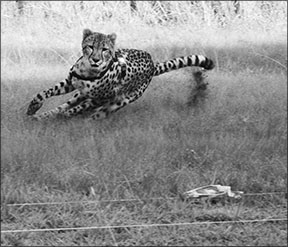

Cheetahs, our domestic cats’ big cousins, seem to fascinate scientists. Maybe it’s because they’re the fastest land animal, and measuring their speed presents a challenge. Researchers have clocked cheetahs running after a lure and observed films of them chasing prey in the wild.

288

Now, with the use of GPS and a motion-sensing collar of their own design, Alan Wilson, BSc, Ph.D., BVMS, and his team at the Royal Veterinary College in London have gathered what they describe as the first detailed information on the hunting dynamics of the cheetah in its natural habitat. Their tracking collar was equipped with a GPS module and electronic motion sensors — accelerometers, magnetometers and gyroscopes — powered by solar cells

and batteries.

They recorded data over 18 months from 367 “hunting events” by three female and two male adult cheetahs in the Botswana Predator Conservation Trust in remote Northern Botswana. The findings: The cheetahs ran at top speeds of 58 miles an hour after prey, mostly impalas. By comparison, according to the Cornell Feline Health Center, domestic cats can sprint at 30 miles an hour for short distances, a remarkable feat in its own right.

Although speed is certainly important to a cheetah’s hunting success, grip and maneuverability are also critical, according to the study published in the journal Nature. (For information on domestic cats’ athleticism, please see “Why Do They Almost Always Land on Their Feet?” in our October 2013 issue. A clue: Like the cheetah, domestic cats have flexible spines.)

The average length of the cheetahs’ run was 189 yards, with the longest ones measuring 611 yards, or about six football fields.

Future study, based on animals’ ranging behavior in the wild, could have practical application in evaluating management of potential wildlife-protected areas, the researchers say.

Assessing the Eyes

Researchers at UC Davis are studying whether new tests for diagnosing and monitoring tear film disorders in humans could be applied to cats. “This information will be of immediate use to veterinarians worldwide because it will allow early diagnosis and treatment of tear film abnormalities in cats (and) minimize ocular pain and the potential for severe or chronic complications,” says the Winn Feline Foundation, the study’s sponsor.

All species have a thin film of tears coating their eyes for comfort, eye health and vision. The film provides corneal lubrication and protection from infection, and flushes debris from the eyes’ surface. “Abnormalities in these tear layers are associated with rapid evaporation of the tears and drying of the conjunctiva and cornea, which is highly painful and potentially blinding,” the foundation says. ❖