fantom_rd | Deposit Photos

Cats hide injuries and pain by instinct, a behavior that is important for survival in the wild. This forces us to be detectives when our cats are ill.

Some cats become aggressive, trying to keep you away from any body parts that ache. A cat in severe acute pain may sit in the back of a space such as a cage at the clinic, stay rigid, and hiss, growl, or strike at anyone who tries to touch her. These same behaviors might be noted at home if your cat is hurt and has hidden under the bed.

It’s important to understand how to recognize and then gauge your cat’s pain, so you can explain the symptoms to your veterinarian.

Chronic Arthritic Pain

Degenerative joint disease is a common cause of chronic pain in cats. Joint pain is underdiagnosed in cats. An observant owner may pick up signs of joint pain, but these can be subtle and develop slowly over time.

Often, signs of arthritis get dismissed as “old age,” but they shouldn’t. You may notice that your cat is reluctant to go up and down stairs, and this is even more noticeable if litterbox use requires the cat to negotiate a set of stairs. “Accidents” around the house catch people’s attention!

Your cat may pass on sleeping on the windowsill in the sun or may no longer want to chase a light. A decrease in self grooming can mean sore joints that make normal grooming painful.

A thorough history showing changes in behavior and radiographs are often required to make an accurate diagnosis of feline arthritis.

The American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAFP) says arthritis is much more common in cats than previously believed. “The most frequently affected joints appear to be the hip, stifle, tarsus, elbow, thoracolumbar and lumbosacral area (spinal areas),” says the AAFP. “For each one-year increase in a cat’s age, the expected total DJD (degenerative joint disease) score increases by an estimated 13.6 percent. Moreover, there is a dramatic increase in the prevalence and burden of DJD beginning at about 10 years of age.”

Surgical Pain

Knowing that a cat will feel some pain post operatively allows your veterinarian to plan pain management even before the pain starts. The injectable opioid buprenorphine provides good pain relief for cats. This medication may be incorporated into the preanesthetic protocol for your cat, administered during surgery, and/or given post op for pain relief. Bupivacaine, a local anesthetic, administered during surgery allows cats to wake up after a spay surgery with much less pain. With less pain, cats get back to normal eating, drinking, and mobility sooner.

The American College of Veterinary Anesthesia and Analgesia notes, “Unless drugs with analgesic properties (i.e., opioids, a-2 agonists, local anesthetics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) are used, rapid recovery from anesthesia is often associated with intense acute pain following a surgical procedure … The more invasive the procedure, the greater the tissue damage and the greater the degree of postoperative pain.” A cat having an uncomplicated spay won’t be as painful as a cat having a broken leg repaired. Surgeries involving the eyes and surrounding structures and dental surgeries can be quite painful.

Local anesthetics applied around the area where the surgery will be performed can serve two purposes. These drugs provide direct analgesia by “numbing” the nerves in the area and allow your veterinarian to reduce the amount of systemic anesthetics needed.

Medications

Dog owners have a variety of NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) available to treat arthritis, but cats have a greater risk of serious side effects. Liver, kidney, and gastrointestinal side effects are common and, in some cases such as acetaminophen, may be fatal. Robenacoxib (Onsior) and meloxicam (Metacam) are NSAIDs that have been safely used in cats. Both drugs have the potential for side effects and should be dosed EXACTLY as prescribed. Only robenacoxib is approved for oral use in cats at this time. Meloxicam is sometimes used “off label” and is approved for use in cats in Europe.

Note: As always, but especially with many pain medications, you need to be sure your veterinarian is aware of any and all medications and supplements your cat is taking, as well as any other health problems she may have. Side effects and drug interactions are common and could prove fatal.

Polysulfated glycosaminoglycan (Adequan) is an injection to help both protect and stimulate healthy cartilage. A variety of nutraceuticals, such as glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate, may help to keep an arthritic cat mobile and comfortable. Omega 3 fatty acid supplements with DHA and EPA can also add to your cat’s wellbeing.

A study from North Carolina State University, published in the July 2016 Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, took a novel approach to treating feline recurring degenerative joint disease. Researchers injected feline-specific anti-nerve growth factor antibodies via subcutaneous (under the skin) injection. The treatment had shown to have analgesic (pain-relieving) effects in rats, dogs, and humans, so the researchers wanted to see if that would extend to cats, and it did. Positive results, with increased mobility, lasted for about six weeks, with no deleterious effects noted.

Support Therapies

Acupuncture is helpful for some cats for pain control (see “Acupuncture for Cats Heads Mainstream,” August 2016, at catwatchnewsletter.com).

Weight loss is highly recommended for overweight cats—discuss a proper weight loss plan with your veterinarian to avoid complications such as hepatic lipidosis, which may occur with rapid weight loss (see “Fat Cats—Obesity Isn’t Fun or Healthy,” December 2017).

If your clinic has a rehabilitation area, laser and underwater treadmill sessions can be wonderful. You may receive exercises to do at home to keep your cat limber as well as some environmental modifications to reduce stress on her sore joints. For more information, see “Feline Physical Rehabilitation,” April 2019.

Manage Pain Using the PLATTER Approach

You may need to try different options to find the pain management plan that works for your cat. The American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAFP) and the American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA) suggest managing a cat’s pain as the PLATTER approach:

PLan – Every case should start with a patient-specific pain assessment and treatment plan from your veterinarian.

Anticipate – The patient’s pain management needs should be anticipated so that preventive analgesia can be provided. If the cat is in pain, treatment should start as soon as possible.

TreaT – Appropriate treatment commensurate with the type, severity, and duration of pain that is expected (acute vs. chronic).

Evaluate – The efficacy and appropriateness of treatment should be evaluated, possibly using a client questionnaire or an in-clinic scoring system. Keep a notebook to write down dates, times, and observations to help your veterinarian devise the perfect plan for your cat.

Return – Arguably the most important step, this action takes us back to the patient, where the treatment is either modified or discontinued based on an evaluation of the individual cat.

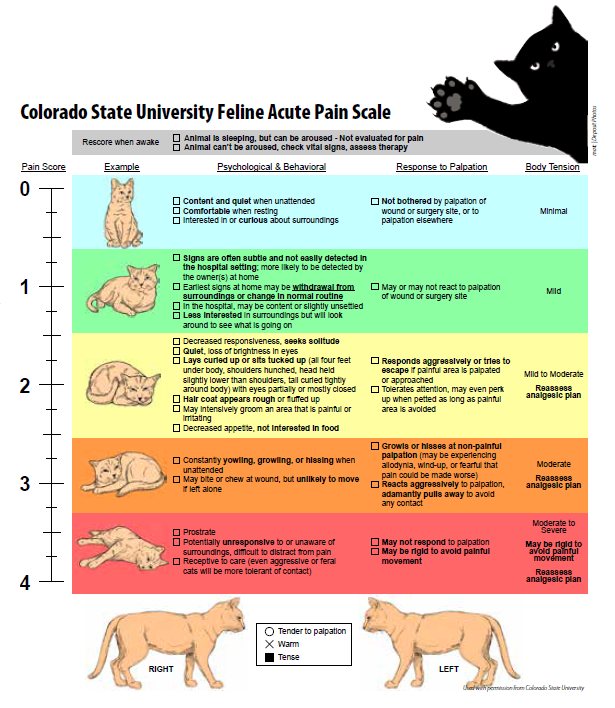

Scales to Help Judge How Much Pain Your Cat Is In

You can gauge your cat’s pain using one of several pain-scoring systems developed for animals. Colorado State University, shown here, and the University of Glasgow both use behaviors to judge an animal’s discomfort, such as when the cat tries to lick at a surgery site, the position of her ears, her body posture, if she is silent, crying, purring, etc. (download a copy at https://tinyurl.com/CSUpain). The Glasgow system uses 28 descriptors in seven categories to rate a cat’s pain. While it is designed for veterinary professionals, you can download a copy at: https://tinyurl.com/Glasgowpain2.

Colorado State University Feline Acute Pain Scale

Click on image to enlarge.