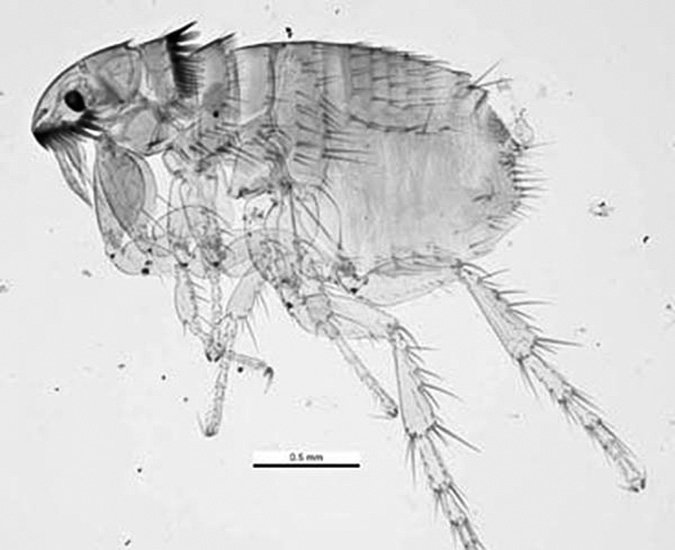

Although high temperatures and humidity are most favorable to the cat flea from June to August, it breeds in the U.S. year-round. Ctenocephalides felis is an intriguing little insect — no more than an eighth of an inch long but capable of jumping eight inches. A female can lay 50 eggs a day on its host. But here’s where intrigue can turn into irritation and beyond:

“Flea saliva, deposited into the skin when fleas feed on cats, contains more than 20 irritating, potentially allergenic substances,” says dermatologist William H. Miller, VMD, Medical Director of the Cornell University Hospital for Animals.

Indoor cats are not immune to infestation. Fleas can arrive indoors on clothes, on dogs or other cats. Their life cycle, occurring over several weeks to months, encompasses egg, larva, pupa and finally an adult with the sole mission of seeking a warm-blooded host — your cat.

That’s when trouble begins. “The flea’s bite causes a red papule — a small bump sort of like a mosquito bite in a person,” Dr. Miller says. “If the cat had only one flea, the animal and owner wouldn’t even notice it. However, fleas rarely occur alone. As a group, fleas can inflict numerous itchy bites. And if the animal is allergic to flea saliva, the bite wound is bigger, angrier and itchier.”

Complications can arise from the bites when the cat tries to soothe the itching by scratching, licking, chewing or rubbing. Serious scratching can damage the surrounding skin, and it can become infected. “In debilitated animals or those with chronic untreated allergies, this secondary infection can seriously damage the skin and cause systemic problems,” Dr. Miller says.

Fleas are also a vector for tapeworms and various bacterial pathogens like Bartonella, Dr. Miller points out.

Treatment for flea allergies can involve steroids, antihistamines and newer anti-allergic medications.